| front |1 |2 |3 |4 |5 |6 |7 |8 |9 |10 |11 |12 |13 |14 |15 |16 |17 |18 |19 |20 |21 |22 |23 |24 |25 |26 |27 |28 |29 |30 |31 |32 |33 |34 |review |

|

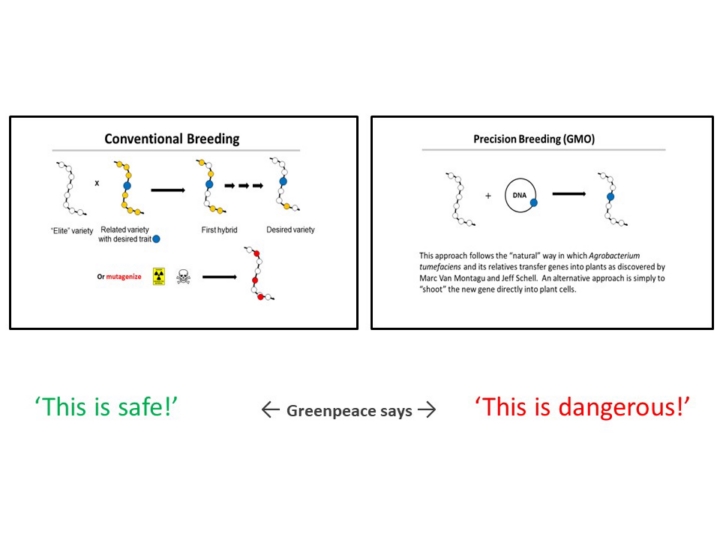

This is the only thing that really relates directly to science that I'll tell you, and this is just for those people who are not scientists in the audience. Conventional breeding, once we figured out what was going on, we realized that we could do the conventional breeding in the lab and so we would work on that and the idea is you've got a nice variety up here that you sell, so this is the one that we're working and selling, but we wanted it to grow a little taller, or we would like it to produce a little more grain than it used to, and so what do we do? We find a wild variety that has the characteristic we want and that is missing in the one that we've been growing at the moment and we make a cross. And after you make the cross the first time around, half of the genes come from the elite variety (those are the white ones that show up here) and half come from the wild variety (those are the yellow genes that show up there). Now, you can pick the ones that have the gene you want, they have the characteristics you want, but they put a lot of other genes in there too that maybe you don't want. And so what you do now, is you keep crossing these hybrids back to the original one so that you keep adding more and more of the original gene set into the hybrids you've been making until eventually you get the desired variety, which is picked by the one that you want (what's happening, okay!) in addition it's also got a lot of other traits that we don't know what they're there for, but they don't seem to affect the way it grows. And so that means you have to realize that when you look at anything that has been traditionally bred, you know some of the things that are in it, but there are plenty of things you don't know. And I'll show you a consequence of that that comes from traditional breeding.

On the right-hand side is the way that Marc von Montague discovered bacteria were able to transfer DNA into plants. He studied something called Agrobacterium and it has a little piece of DNA in it (we call it a plasmid) that is in the bacterium and this bacterium has figured out how to get it into the plant cell that the agrobacterium likes to grow on. And what Marc realized well was that if this plasmid would do it naturally, and we do it with genes that were already on the plasmid, perhaps we could take a gene that we wanted to put in the plant, put it on the plasmid and use the agrobacterium to put it into the plant. He did that, it worked really well and this was the basis of what are now called GMO's (Genetically Modified Organisms). This is not something that is unnatural, this is what nature does all the time and we now know as we have been sequencing the genomes of some of these plants, we realize they picked up genes from all sorts of things that we had no idea about before. This is something that goes on in nature all the time. Yet Greenpeace will argue that this is inherently dangerous where you take one gene, you know what it is, put it into the plant, this is very dangerous. You take a load of genes, mix them up, end up, this is okay, this is fine. And why? Because we have been doing it for a long time and we've never really looked to see whether these plants are all safe or whether they're not. |