| front |1 |2 |3 |4 |5 |6 |7 |8 |9 |10 |11 |12 |13 |14 |15 |16 |17 |18 |19 |20 |21 |22 |23 |24 |25 |26 |27 |28 |29 |30 |31 |32 |33 |34 |35 |36 |37 |38 |39 |40 |41 |42 |43 |44 |45 |46 |47 |48 |49 |50 |51 |52 |53 |review |

|

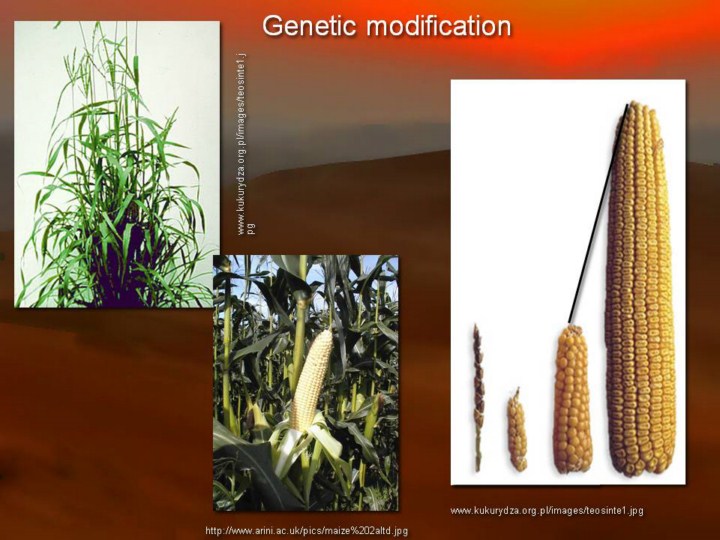

But even before science and technology entered the agricultural arena, humans had made some spectacular progress in the genetic modification of plants to make them more suitable as human food. Corn (also known as maize) came from this grassy relative, called teosinte. *Corn and teosinte are so different that they were originally assigned to different species. And yet these two plants are so closely related that they can be crossed and the *off-spring are everything from what looks like the teosinte rachis, with its hard-as-rock seeds, to small and medium-sized ears of what is recognizably corn. Over thousands of years, people have converted this grass to one of humankindís most productive crop plants. The truly dramatic *expansion of the ear took place largely during the 20th century, when it was discovered that seeds from a cross between two highly inbred, rather small and weak plants gave much more vigorous plants with much bigger ears in the first generation. This is called hybrid vigor and is the basis of our current extraordinarily productive hybrid corn varieties.

|