Subscribe to Pittwire Today

Get the most interesting and important stories from the University of Pittsburgh.Using Novel Stent, Pitt Researchers Aim to Double Number of Successful Organ Donations

Each year, the United States experiences an extreme shortage of organ donations, and many transplantable organs stop receiving vital blood flow after a donor’s heart fails.

“It’s a big dilemma,” said Bryan Tillman, assistant professor in the Division of Vascular Surgery at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. “Over 116,000 people are waiting for an organ, and only 25 percent of those people are actually going to get one.”

However, Tillman and other researchers at the University of Pittsburgh aim to potentially double the number of successful organ donations by developing a novel stent to maintain blood flow to organs, even during the donor’s final heartbeats.

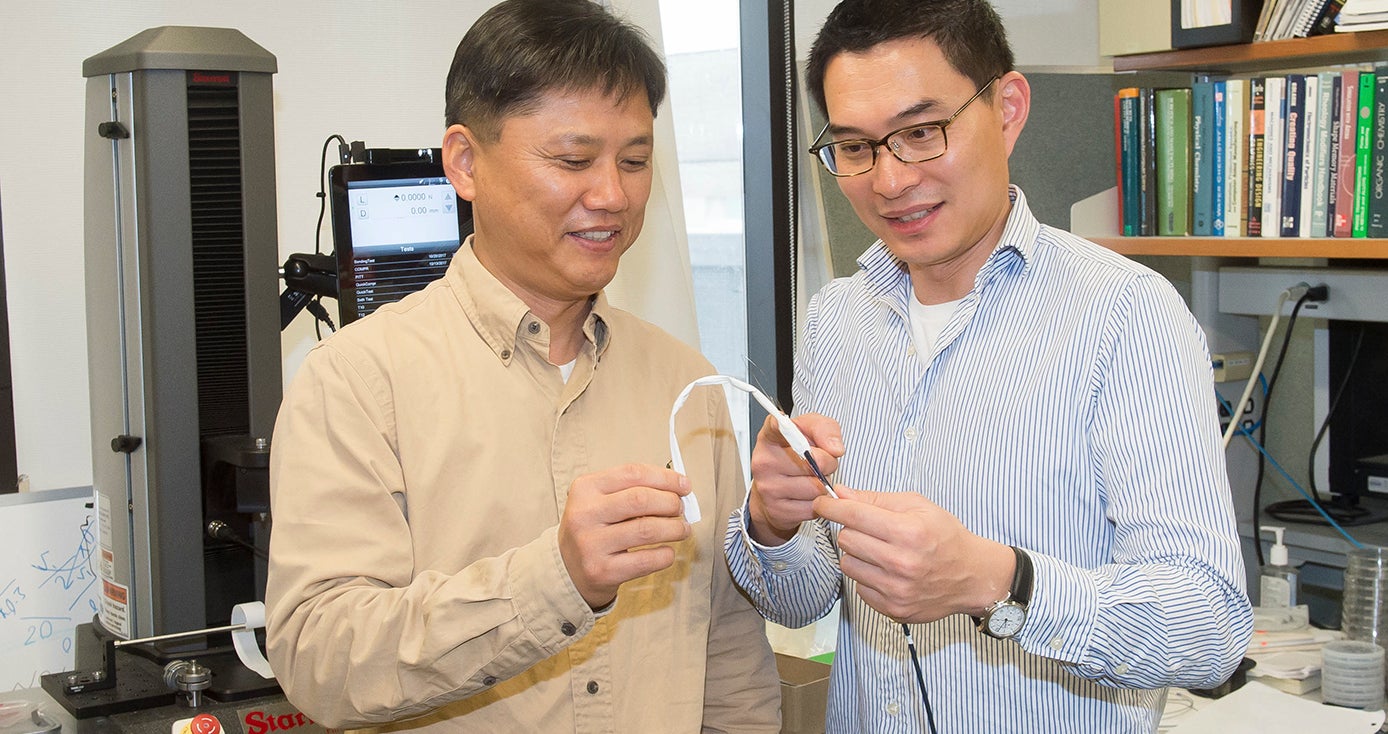

The Department of Surgery is collaborating with the Swanson School of Engineering for the study, which will develop a stent made of smart material to direct selective blood flow during transplant surgeries to target organs, keeping them fresh and usable for patients in need.

The stent will isolate visceral arteries — which supply blood to many major organs — without disturbing the heart. To make the stent, the research team will use a superelastic biocompatible material called nitinol, or nickel titanium, with a shape-memory effect. Nitinol’s mechanical properties allow it to become stronger in higher temperatures.

“After the stent is put into the body, the body temperature activates the deployment,” said Chun. “It changes the stent’s mechanical properties to become superelastic, creating a self-expanding endovascular device.”

The stent can be inserted by a clinician into the femoral artery, located in the thigh, after the delivery of a guide wire and a catheter.

This small puncture or “needlestick” method allows clinicians to maintain selective blood flow to certain organs without disrupting others’ natural functioning. The much larger organ stent, when compressed, can be delivered to the desired organ and deployed.

Transplants involving major organs connected to the main aorta could benefit from this new technology, with the researchers being able to target the kidneys, pancreas and liver.

“We hope this development in technology will contribute a lot for patients,” Chun said.

“We believe this is promising,” Cho added. “Eventually, we hope to commercialize this device to benefit people.”

Other collaborators include William C. Clark, professor of mechanical engineering and materials science at Pitt; Ryan Dzadony, associate director of the UPMC School of Perfusion; Anthony J. Demetris, Starzl Professor of Liver and Transplant Pathology at UPMC; and Amit Tevar, associate professor of surgery at the Thomas E. Starzl Transplantation Institute.

The four-year project is being funded by a $1.3 million grant from the National Institutes of Health.