Subscribe to Pittwire Today

Get the most interesting and important stories from the University of Pittsburgh.Project Aims to Recycle the Unrecyclable

Each year, more than 8 million tons of plastics, ranging from newly dumped containers to broken down microparticles, enter the ocean, forming large “garbage patches,” according to the nonprofit Plastic Oceans Foundation.

“It all either goes to the landfill or it floats around in the environment and it doesn’t degrade,” said Eric Beckman, Distinguished Service Professor and co-director of the University of Pittsburgh’s Mascaro Center for Sustainable Innovation. “It’s a major issue when you start looking at the numbers because they are so large, and plastics have been making their way to the seas for almost a century.”

One solution to this growing crisis is to prevent plastic from becoming waste to begin with — and researchers from Pitt’s Swanson School of Engineering aim to do just that as the only university team to win the international Circular Materials Challenge.

Beckman, along with Assistant Professor Susan Fullerton and Associate Professor Sachin Velankar, is looking to create a material that can replace types of plastic packaging that can’t be recycled due to their use of various layers of materials that can’t be separated.

The team, all from the Department of Chemical and Petroleum Engineering, was recently recognized at the World Economic Forum Annual Meeting in Davos, Switzerland, where Beckman accepted a $200,000 prize from the Ellen MacArthur Foundation and tech accelerator NineSigma for the game-changing idea.

“It’s both really cool and really intimidating,” said Beckman, reflecting on the team being the only academia-related winners in Davos. “But they really liked our concept because it addressed what they saw as a crucial need. Since the invention of the first synthetic polymer in 1907, plastic has become an extremely versatile, economical and dynamic product that isn’t just going to disappear overnight. So, we need to take a 21st-century approach to make it a more sustainable product.”

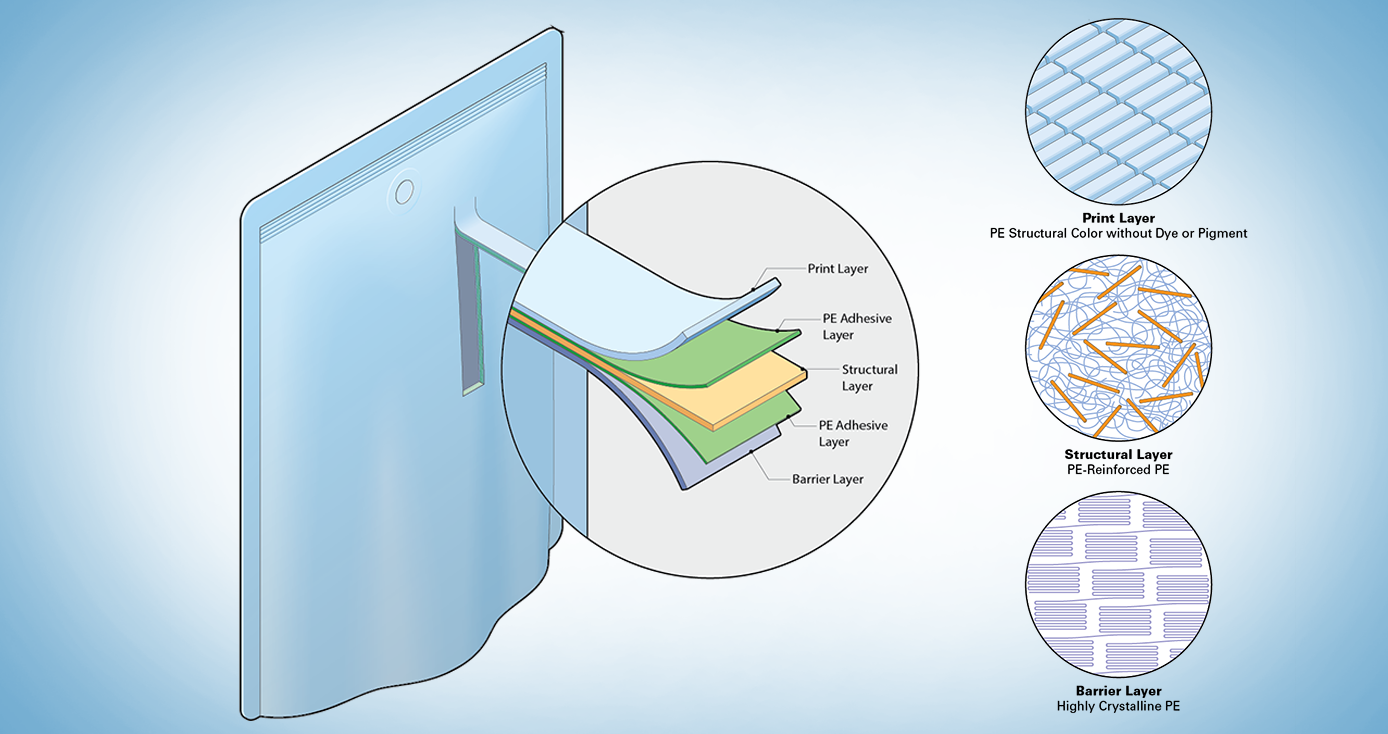

Some plastics currently used in food and beverage packaging are unrecyclable because of the materials used to maintain freshness, block UV light and hold inks for labeling, among other functions. Bound together by adhesives, these different layers of “barrier packaging” cannot be easily separated and therefore cannot be recycled.

The Pitt team’s solution is to alter the microstructure of polyethylene — simple plastic — to mimic the properties of other complex materials in current laminate packaging. Since the basic chemistry of each layer would remain polyethylene, the packaging could then be collected with other plastics and recycled using traditional methods, removing it from the waste stream.

The team will use commercial polyethylene resin in the lab and will first focus on creating a sustainable oxygen barrier to maintain freshness in food and beverage products. Also, as part of their MacArthur prize, the Pitt researchers will join a 12-month accelerator program in collaboration with California-based Think Beyond Plastic, working with its commercialization experts to make this project marketable at scale. The team will also search for additional project funding.

The need for more adaptive packaging is critical: By 2050, oceans are expected to contain more plastics than fish (by weight), and the entire plastics industry will consume 20 percent of total oil production and 15 percent of the annual carbon budget, according to a 2016 report from the World Economic Forum.

Beckman said while this research will be challenging, he hopes the team’s design will not only set a new standard for high-performing and recyclable plastics, but also stimulate people to think about other ways they can transform molecular products to services by mirroring nature and taking advantage of nanostructure building blocks.

“We now have a better understanding and the technology to manipulate polymers at the micro- and nanolevels, and so we think this will enourage other researchers and even industry to reconsider the historic methods of plastics manufacturing and take a more systems-based approach,” Beckman said.