| front |1 |2 |3 |4 |5 |6 |7 |8 |9 |10 |11 |12 |13 |14 |15 |16 |17 |18 |19 |20 |21 |22 |23 |24 |25 |26 |27 |review |

|

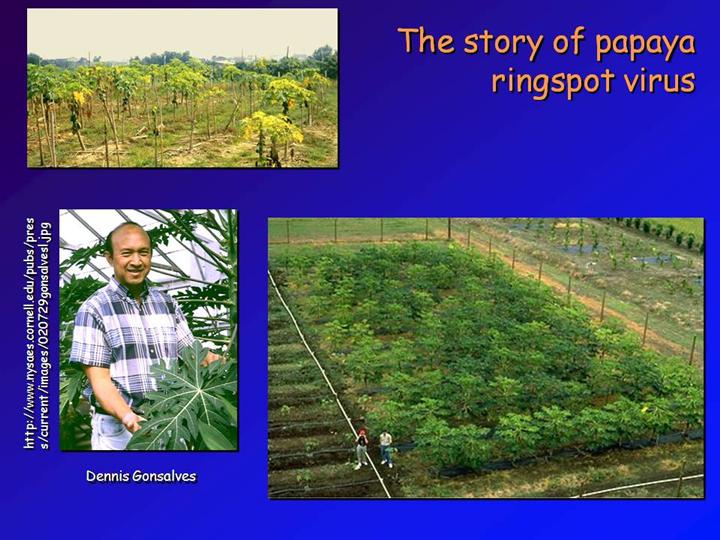

PRSV was first discovered in Hawaii in the 1940s. Within a decade it had wiped out Oahu’s papaya industry, which then moved to the big island of Hawaii and was kept relatively free of the virus for several decades by constant vigilance and rapid elimination of infected treas. The hero of this story is a plant pathologist by the name of Dennis Gonsalves. He heard that a colleague in St. Louis, Dr. Roger Beachy, had used the kinds of molecular techniques illustrated in earlier slides to introduce a viral gene into tomatoes and found that it protected them from infection. Gonsalves had worked for many years to derive PRSV-resistant papaya varieties, but was never successful using traditional techniques that plant breeders use -- and neither had anyone else in the world. So he decided to try this new molecular approach. Papaya’s aren’t easy to transform with agrobacterium, but he persuaded a colleague of his, Dr. John Sanford, to try using his newly invented gadget that he called a “gene gun” to introduce a viral gene into papaya plants. The so-called gene gun shoots tiny, tiny particles of gold coated with DNA through the plant cell wall into cells. There, some of the DNA molecules enter the nucleus and get incorporated into the DNA. It wasn’t easy. It took them more than a decade, but the first virus-resistant plants were ready in 1991 and by 1992 they had received permission to carry out the first field trials. At about this time, the virus was beginning to get out of control and do a lot of damage to the papaya plantations on the big island. The top left picture shows you what an infected field looks like. A couple of years later, the USDA gave them permission to do large-scale field tests (lower right). But then it took another 3 years to get through all of the safety testing required by the USDA, the EPA, and FDA. By that time, many farmers had simply gone out of business. Fortunately, the story has a happy ending. The USDA had allowed them to grow seeds, although they could not give them out until the regulatory requirements were satisfied. The seeds were finally released in 1998, free of charge to growers and by 2000, the Hawaiian papaya industry had come back to pre-1995 production levels. |