| front |1 |2 |3 |4 |5 |6 |7 |8 |9 |10 |11 |12 |13 |14 |15 |16 |17 |18 |19 |20 |21 |22 |23 |24 |25 |26 |27 |review |

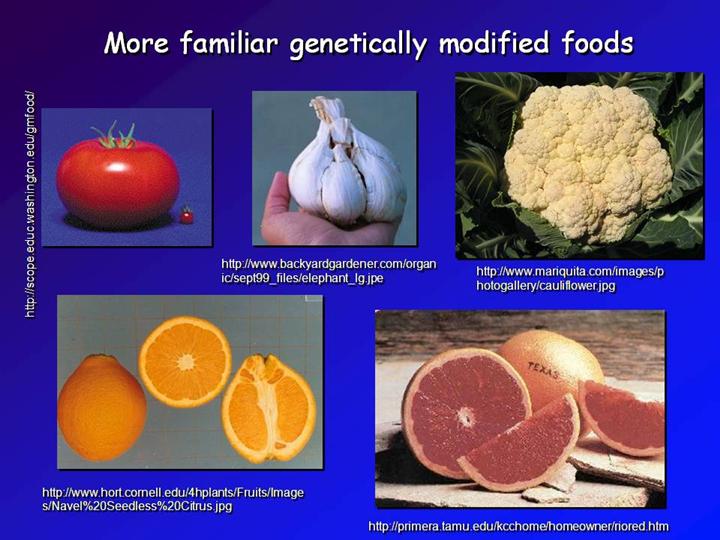

http://scope.educ.washington.edu/gmfood/ http://www.backyardgardener.com/organic/sept99_files/elephant_lg.jpe http://www.mariquita.com/images/photogallery/cauliflower.jpg http://www.hort.cornell.edu/4hplants/Fruits/Images/Navel Seedless Citrus.jpg |

Here are more familiar examples of plants that were genetically modified to produce today’s food crops. The big, red lush tomatoes were derived from tiny, seed pods, as illustrated in the upper left panel. In the upper middle is elephant garlic, developed during the 20th century by plant breeder Luther Burbank. On the upper right is cauliflower, which is a mutant plant of the cabbage family that makes endless numbers of flower buds. On the lower left is a seedless orange, a mutant variety that cannot reproduce on its own because it cannot make seeds. Such plants are propagated by grafting cuttings onto root stocks of related varieties. And on the lower right is Rio Red grapefruit, which was produced by irradiating grapefruit shoots at the Brookaven National laboratory, then planting them and identify mutations (caused by the irradiation) that resulted in redder fruits. The bottom line is that plants are quite maleable genetically and people have used that property to increase their human food value using both mutations that occur naturally and mutations that can be induced by chemicals and radiation. (People have done the same with many animals -- just think of the many breeds of dogs we have today.) But neither spontaneous nor induced mutations are directed. Moreover, most mutations are harmful to the organism. So identifying useful mutations from among the many deleterious mutations requires a great deal of effort. |