clock escapements

John D. Norton

Center for Philosophy of Science

Department of History and Philosophy of Science

University of Pittsburgh

This page at www.pitt.edu/~jdnorton/Goodies

clock escapements

There is a competition, the "Flame Challenge," underway at the time I write these words for the best answer to the question "What is time?" The target audience is eleven year old children and children of this age will be the ultimate judges. (pdf of screen, December 23, 2012).

In one sense, the competition will be a great success. It will be an occasion for many scientists--the only people allowed to answer--to write some engaging prose related to time or to produce some entertaining graphics on time. There will be some wonderful entries.

The challenge is introduced with a perfunctory and familiar disclaimer. First comes a celebrated quote from Augustine

“What then is time? If no one asks me, I know what it is.

If I wish to explain it to him who asks, I do not know.”

– Saint Augustine

The sentence that follows arrives with reliability that night follows day follows night and was offered, I expect, without reflection. Doesn't everyone know that...

It’s a deep question, and it has no simple answer.

Is that really so?

clock escapements

What is time?

There will be many delightful responses to the challenge. However, I am confident to predict, none of them will answer the question properly. (See below for an update.) The most successful entries will treat the question merely as an excuse to write or display an answer to some other question. They will treat "What is time?" as an open ended prompt. It will be for them the scientific equivalent of "So, tell me, how are things?" It will be an exercise in creative misdirection.

Why am I so confident? The reason is that the question "What is time?" as asked is not really a scientific question at all.

The question is readily confused with other eminently scientific questions, each of great interest. They include questions like:

Does time have a beginning?

Does time have an end?

If our molecular microphysics does not distinguish future from past, why

does ordinary, macroscopic physics?

How do our notions of time change when we accommodate them to special

relativity? To general relativity? To quantum theory?

These questions and many more like them will be answered in the best responses to the challenge.

What about "What is time?" ?

Now I can come to the real point of my piece. People outside philosophy of science often wonder just what philosophers of science do. Where does the work of the scientist end and that of the philosopher of science begin? This question on time provides an illustration.

clock escapements

Scientists trying to answer this question will almost invariably start by trying to deflect the question. If you ask them the question, you may first get the rather superficial quips:

"Time is what clocks measure."

"Time is what stops everything happening all at once."

They are not real answers, but merely amusing retorts that often serve to quieten an annoying questioner.

A more serious attempt to answer will tell you not what time is but about some interesting temporal phenomenon.

In his special theory of relativity, Einstein showed that different observers can disagree on which of two events happened first and that can happen with neither being wrong. Or in his general theory of relativity, we learn that space and time together have a geometry and that its curvature is gravity. Or we learn from thermal physics that time increases with a thermodynamic quantity, entropy, under the guidance of the Second Law.

This may satisfy you. Or you might press harder and complain that these responses only report some facts about time. But they do not say what time IS. What IS time? you insist.

This display of stubbornness will likely be met with awkwardness. The conversation may end with a cough or another deflection. The answering scientists will be able to proceed only if they adopt a different style of analysis. That is, they will need to approach the question "What is time?" like a philosopher.

How bad can the deflections

and evasions be? Look at

"What Is Time? In their Own Words: 14 Experts on Time." Or, if the

link doesn't work, look here.

clock escapements

How do philosophers approach this question? Or at least how do philosophers of science of my stripe do it? They are much less confused by the question. They see that the core difficulty is that "What is time?" is itself a bogus question or, to use the more technical term beloved by philosophers, it is a pseudo-question.

This way of thinking about the question has a venerable pedigree. See Friedrich Waismann, "Analytic-Synthetic II, Analysis, 11, (1950), pp. 25-38, on pp. 26-27.

The grammatical form of the question makes it look like other simple questions such as:

"What is the Atlantic Ocean?"

"What are submarines?"

"What are stars?"

"What is the Leidenfrost effect?"

All these questions admit straightforward answers: a certain body of water; a boat that goes underwater; very hot balls of gas; what happens when a water drop is suspended above a very hot plate by a layer of vapor.

The question "What is time?" has no corresponding answer. The "IS" question demands that we identify time with something else typically but not necessarily better known to us, much as we identify submarines with boats that go underwater. The very asking of the question in this illicit form is what makes time mysterious.

To proceed, we need to separate two ways that this "IS" question can be asked.

clock escapements

This is the every-day form of the question and one that was likely originally intended for time. It is a request for a substitution by other notions already familiar in the same discourse.

We might ask "What is a ketch?" The answer is that it is a two-masted sailboat, rigged fore-aft with triangular sails, with the smaller mast aft.

What is distinctive in the response is that each of the notions employed in the answer are presumed already known to the questioner.

When the question "What is time?" is asked in this mode, the exercise degenerates into a circular word game. There is no answer in our ordinary vocabulary that does not already have the notion of time in it.

The simplest way to see this is to consult a dictionary for a definition of time. For example, you will find:

"the system of those sequential relations that any event

has to any other, as past, present, or future;..."

(dictionary.com)

This is about as good as a definition as you can get. However the circularity is quite evident the moment you ask just: just what is an event, as opposed, to a thing. Or what is past, present and future, as opposed to left, center and right?

No answer is possible unless we use sentences that employ the word "time." Or, at best, we use sentences with another synonym for time that merely postpones the manifestation of the circularity.

The quips listed above do no better at avoiding the circularity.

"Time is what clocks measure."

What is a clock as opposed to a teapot?

"Time is what stops everything happening all at once."

What is it to happen? How does "at once" modify it?

It takes only a little playing of this game to realize that breaking out of the circularity is impossible. We have reached a kind of linguistic bedrock with the term "time" such that we cannot go deeper.

This troublesome circularity is the basis of Augustine' lament above; or at least it is the reason that the lament can continue in our repertoire of purportedly deep truths.

clock escapements

What does this failure mean? Does it mean that this innocent question has pressed us to confront a dark and shameful chasm in our knowledge?

Hardly.

Average eleven year olds have a pretty firm grasp of temporal phenomena. They understand quite well how today differs from tomorrow and yesterday; that an hour is much longer than a minute; how to use a clock to coordinate a meeting with a friend at 11am sharp; and much more. Our ordinary knowledge of time resides in a huge collection of banal facts of this form. There is no mystery in them. There is just the banality of ordinary temporal life.

The mystery only comes when we demand that someone say what time IS. We are suddenly to imagine a something, somewhere that somehow is responsible for everything temporal, much as our imaginations form images of the wild beast in the tower responsible for the terrible howls at night.

The mystery is created by a hidden presumption in the question. Our familiar repository of ordinary temporal facts somehow fails us, we are supposed to think. It is not telling us what time IS. There is something more that has not been said that needs to be said, we find ourselves thinking.

But there is nothing more. There is nothing extra needed. We understand time perfectly well already.

It is curious that we allow the question to stand. The question demands an answer when no answer can be given. We have heard these questions before and know how to deal with them. They are impossible to answer since they have presumptions buried in them that preclude answers. We dismiss them as frivolous word games and do not, or should not, mistake their impossibility as resting on some deep truth or hidden wisdom.

What happens when an irresistible force meets an immovable object?

The collision can never happen since you cannot have both this force and this object. If you have one then the other is impossible. The trick is to get you to accept that both are simultaneously possible.

What is the sound of one hand clapping?

The trick presumption is that there is a sound, whereas we know that one hand cannot clap by itself.

Just where is cyberspace?

The trick presumption is that we must supply a geographic location like "At the intersection of Bigelow and Fifth Avenue" or "on Brunot's Island."

clock escapements

There is a second way this question might be asked. It is a request for new knowledge that goes beyond what we already know, typically in the form of a new physical theory.

What is a cloud?

...Tiny droplets of water that scatter light.

What is air?

...A mixture of roughly four parts nitrogen gas, one part oxygen gas and a some other gases in lesser amounts.

What is light?

...The propagation of a wave-like disturbance in the electromagnetic field; and the energy of the disturbance may be partially localized spatially in quanta or photons.

Each of these answers calls up new notions of successively greater scientific sophistication. The question "What is time?" may be answered in this mode as well. There is a naive expectation that the fancy theories of modern physics somehow do a better job of answering the question without the circularity of the familiar substitutions just sketched.

clock escapements

Do these new theories do any better with the original circularity?

They do not. However the failure is harder to see since the fancier theories surround familiar notions in a fog of novel terminology and conceptions.

Perhaps we might be assured that time is really just one of the dimensions of a four dimensional spacetime manifold. Or that all that really exists are events or processes and time arises from how they are arranged. Or that there are causal orderings of things and time flows along them.

These proposals and many more like them are erudite and impressive. If they are correct, we are certainly learning something new about time.

But we are doing no better than we did with the original circularity. A four-dimensional manifold is just a set whose elements can be continuously labeled by four numbers. What makes some candidate four-dimensional manifold a spacetime manifold as opposed merely to some four-dimensional space with no association with time?

We can only identify it as a spacetime if we know how to connect the manifold in the right way to things in the world so that one dimension has a temporal character. But doing that already requires that we know what is temporal. The circularity has returned.

clock escapements

We return to the competition. The challenge is well-conceived precisely because the question admits no appropriate answer. It must be answered by creative diversions, none of which can be judged unequivocally to be the complete and correct answer. It will be intriguing and entertaining to see just what the scientists can offer.

There will be plenty of good science and plenty of good pedagogy in the responses.

While there will be good science, the challenge will perpetuate bad philosophy. It will reinforce the idea that deep foundational thinking--the proper domain of philosophical analysis--resides in posing questions that we find so awkward that we do not answer but must evade them with clever ripostes or diversions.

Those who pay no attention to philosophical analysis will find the question "What is time?" mysterious and challenging and will struggle to understand just why it is so hard to provide a proper answer. They may even lament that it is a deeply philosophical question, thereby conveniently banishing it from those questions they feel a professional obligation to answer.

Philosophers, or at least those like me, will have little trouble in identifying the mystery and challenge as one that is cheaply gained. We are asked a pseudo-question that is so laden with hidden presumption that no direct answer is possible.

Bad philosophy of science takes confusing questions and fails to answer them clearly. It misdiagnoses the failure as a symptom of the great philosophical depth of the question.

Good philosophy of science takes the same confusing questions and talks through them until the mystery is gone and one wonders why anyone was ever confused by them in the first place.

I set aside the tiresome traditions in philosophy that try to argue that time is unreal, an illusion or perhaps some byproduct of how we connect with the true, timeless but mysteriously elusive reality. These traditions are mere cleverness, untempered by common sense. They show that even smart philosophers are as capable as any myth maker of losing themselves in fantasy worlds of their own creation.

(Added February 14, 2018)

The winning video and the winning text entries have been posted at https://www.aldacenter.org/flame-challenge-what-time

The primary substance of the video is the idea that space and time together form a four-dimensional entity, spacetime, and that time is one of its coordinates. It differs from the other coordinates in that we cannot move freely in it. There is also some irrelevant, goofy humor designed to appeal to eleven year olds. I would like to think the eleven year old judges found the goofiness insulting, but I fear they did not.

The winning text entry reads:

What is time?

Have you ever heard your parents say to you that it’s time to go to bed or

time to get up, time to go to school, time to clean your room, time to do

this, time to do that, and on and on. Our world runs on a time schedule,

and the schedule is so tight that there are schedules for everything we do

throughout the day and clocks that tell you what time it is so we can do

those things at the correct time. Time is so obvious in our lives that no

one questions it. It’s just there, we have to live with it, and so we

accept it. All activity on earth is based on time, and this time is what

happened a second ago, a minute ago, an hour ago, days ago, and years ago.

Well, now we have an important question. What is it?

Time has a lot of definitions; like time is history or time is age. But,

have we ever considered a good definition? I have. Here’s my definition.

And no, I did not get this from some book or online. It’s just something

that makes sense to me. I think of time as Forward Movement. Think about

it! Everything moves forward, from the universe to every second of your

life. And because everything moves forward, man developed a way to keep

track of this Forward Movement and called it time. Man also invented

clocks to keep a precise log of this Forward Movement in years, days,

hours, minutes, seconds, and even parts of seconds. I’ll always continue

to think of time as Forward Motion. I’ll also think of it as a Forward

Motion that will never change, will never stop, and can never be reversed.

The original circularity of Augustine's question remains. What is movement or motion? Is movement just change in time? How can it be explained to someone who does not already know what time is?

Overall I am quite disappointed with the winning entries. They are distinguished not by any creative pedagogic flair, but by their banality. Merely reporting some easy facts about time is far from answering the question posed, "What is time?" It is sobering that these were the winning entries. What did the others say? We see that at least some scientists are ill-equipped to handle some simple philosophical analysis.

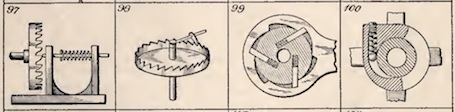

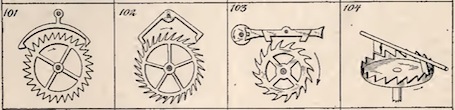

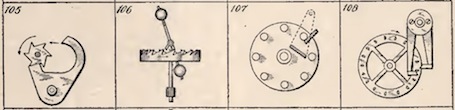

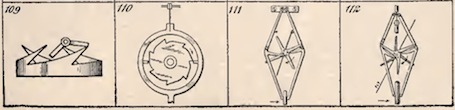

The images are clock escapements from A.A. Hopkins and R.A Bond, Scientific

America Reference Book. New York: Munn, 1914, p. 531.

http://archive.org/details/americscientif00hopkrich "Not in copyright" .

December 23, 2012. February 14, 2018. Copyright John D. Norton.