Subscribe to Pittwire Today

Get the most interesting and important stories from the University of Pittsburgh.On April 28, the Pitt School of Public Health unveiled a free, public exhibit displaying historical documents and laboratory equipment from the lab of Jonas Salk, part of a gift to the University from the Jonas Salk family. The items tell the story of the pioneering work done by Salk and his team to research and test the first polio vaccine.

Here are some highlights you’ll see as you walk through the exhibit — from an iron lung to a desk that traveled across the country twice.

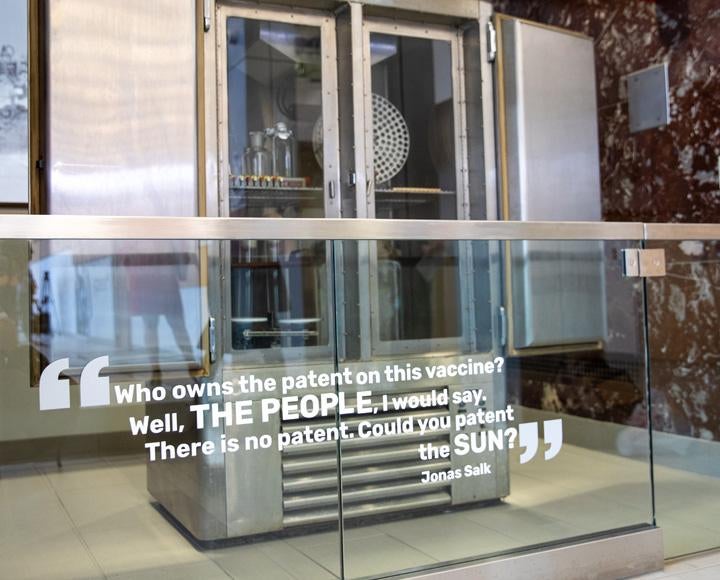

The incubator

One of the first things you’ll see when you walk into the School of Public Health Building’s lobby is a sturdy metal-and-glass case full of laboratory equipment. Look closer and you’ll see that case is actually an incubator, a device that keeps cell cultures at the right temperature.

Displayed inside you’ll find a scale, glass bottles, syringes and other equipment from Jonas Salk’s laboratory, mostly from the 1950s. Keep an eye out for a set of slide cases with a Pittsburgh label.

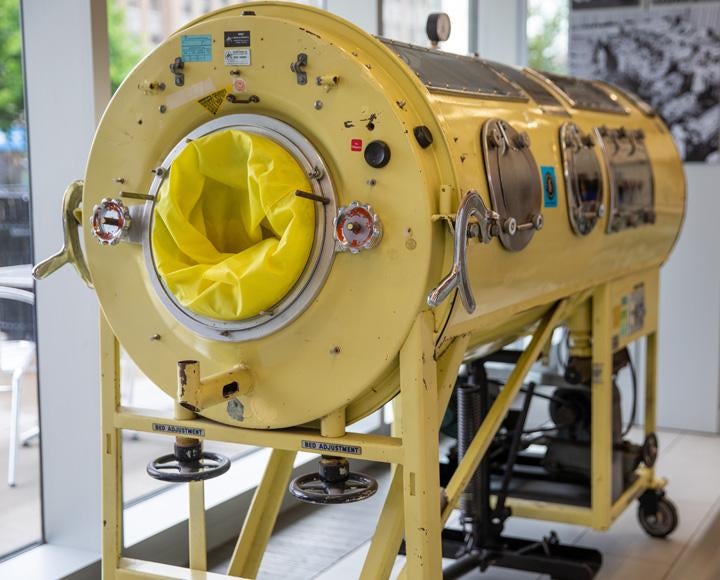

The iron lung

Displayed along the lobby windows is a hulking, custard-yellow cylinder: an “iron lung,” also called a tank respirator, which was once used to help paralyzed polio patients breathe.

Although the tank wasn’t part of the donated collection, it’s an important part of the exhibit, according to Alex Taylor, a history of art and architecture professor in the Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences who helped curate the exhibit along with collaborators in the School of Public Health and a team of students.

“We want the objects to help viewers imagine the urgency that propelled Salk’s lab in the 1950s,” Taylor said. “By placing the iron lung near the lab equipment, we recall the former Pittsburgh Municipal Hospital where vaccine development progressed on one floor while polio patients were treated with iron lungs on another.”

[Students took a leading role in Pitt’s Jonas Salk exhibit.]

Jonas Salk’s desk

Head upstairs and you’ll see what in a different context would seem unassuming: a sturdy-looking metal desk that Salk himself sat at when developing the polio vaccine and even took across the country with him. “As we looked for photographs to try to understand when he started using it, we found photographs in his office at Pitt and at La Jolla in San Diego,” Taylor said.

The desk is free for anyone to sit at, with only a sheet of glass protecting the surface. The team weighed more traditional approaches for displaying the desk but ultimately decided to display it as an interactive piece.

“The value of getting people to use that experience of sitting at his desk to imagine the possibilities of creating something incredible — I think that’s worth the unavoidable impacts on the object over time,” Taylor said.

A Disneyland award

When sitting at the desk, your gaze naturally drifts upward to a wall packed full of awards and accolades Salk received as a result of his work, drawn from the Jonas Salk Papers in the University Library System.

“He was a celebrity. There’s a range of recognitions that give you a real sense of his fame,” said Taylor. “That wall for me was the most fascinating part of the exhibition.”

Among heavy-hitting awards — a presidential medal of honor, for one — you’ll find recognitions in multiple languages, honorary degrees, medals, a celebratory plate and even an “American Hero Award” from Disneyland.

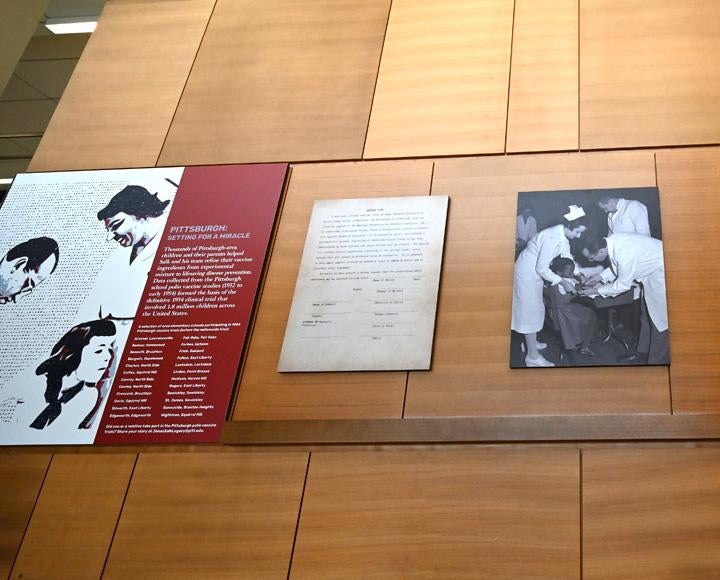

A vaccine consent form

On your way out of the lobby, take a look at the wall — alongside a display of newspaper articles, you’ll see a consent form that parents in Allegheny County signed to allow their children to be injected with the vaccine.

Next to the form hangs a list of Pittsburgh-area elementary schools that participated in vaccine trials before the nationwide rollout. It’s a reminder that even though the exhibit bears Jonas Salk’s name, it was the involvement of not just scientists, but children and parents, that eradicated polio in the U.S.

— Patrick Monahan, top photo by Aimee Obidzinski