Subscribe to Pittwire Today

Get the most interesting and important stories from the University of Pittsburgh.Patients at Severe End of the Autism Spectrum Find Support at Specialty Clinic

This story, written by Carrie Arnold, is excerpted from the fall 2018 issue of Pitt Med magazine.

David and Emily Tate had run out of options.

Since the birth of their daughter, Joy, 16 years ago, the Tates had struggled to manage her sudden, intense outbursts that grew into a tsunami of fury and frustration. Joy, who is on the autism spectrum, didn’t always have the ability to express her needs and understand the tumult of emotions that coursed through her young body. Despite the best efforts of her parents and a cadre of teachers, therapists and psychiatrists (Emily stopped counting professionals at 15), Joy’s emotions daily whirled her into a destructive force that no one could contain or control. Most local psychiatrists couldn’t or wouldn’t help. The family would sit in local emergency rooms when Joy was in the throes of rage only to be sent home because the psychiatric unit wouldn’t take teens with autism. Probably about one-third of people with autism demonstrate severe behavior issues like Joy’s. Behavioral meltdowns can become so extreme in this subgroup that one in three are hospitalized for psychiatric reasons before their 18th birthdays.

Emily and David placed their hopes in an Ohio residential treatment facility for teens on the spectrum, a three-hour drive from their home east of Pittsburgh.

“It was one of the hardest things we ever had to do,” Emily says.

While Joy was there, her behavior deteriorated even further. One week into her stay, a late-night phone call from the facility informed the Tates that Joy had gotten so violent they had no choice but to hospitalize her in a psychiatric unit. The Tates had heard of UPMC’s Merck Inpatient Unit for people with neurodevelopmental disorders, but their insurance would never approve a stay — until now. At the time, Joy’s parents thought this was the worst thing that could happen to their daughter.

But what started as an awful turn of events became a glimmer of hope. When Emily and David arrived in Pittsburgh to visit Joy, they met with psychiatrist Joseph Pierri. From that moment, everything changed.

“If we wouldn’t have met Dr. Pierri, and [Joy] wouldn’t have made it to the Merck center, I don’t think we would be where we’re at today,” David says.

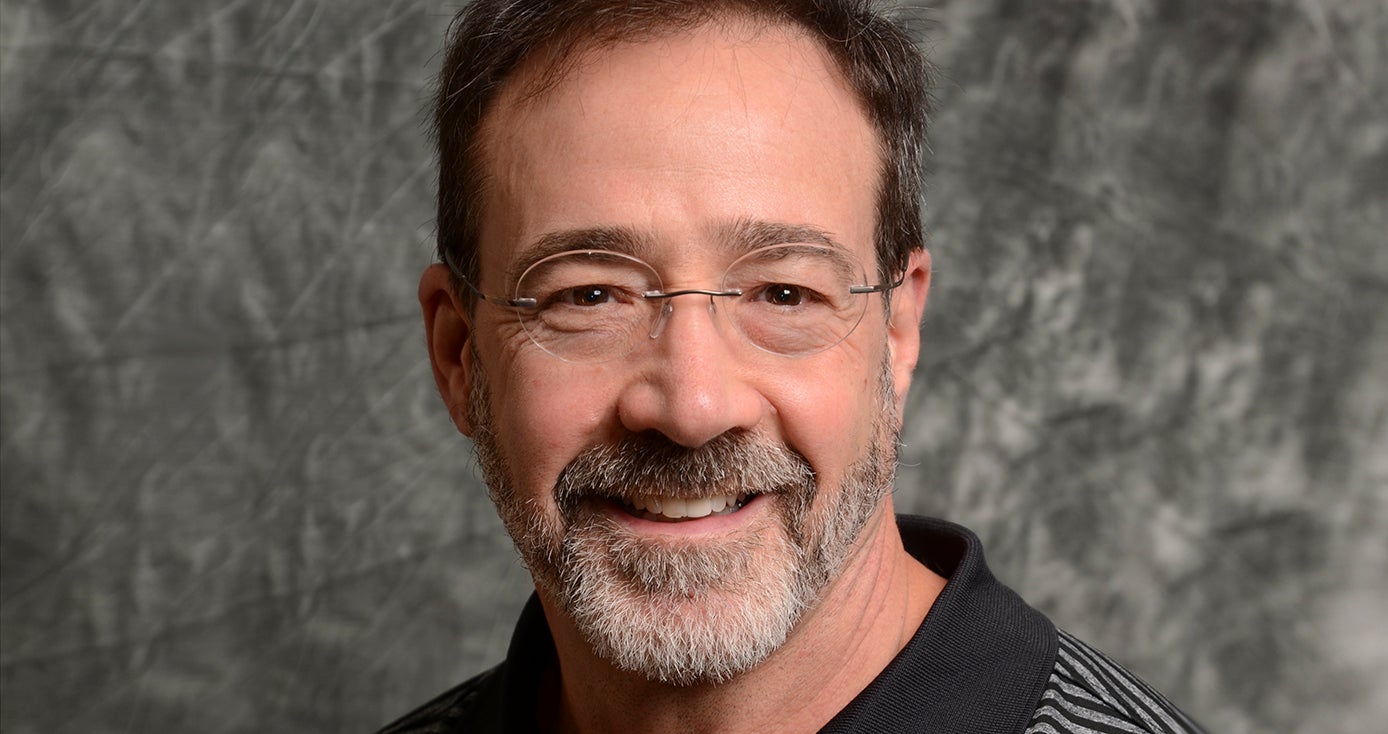

A bespectacled, soft-spoken University of Pittsburgh assistant professor of psychiatry with a salt-and-pepper beard, Pierri is one of the many Merck providers who becomes the calm in the storm for families of children with autism whose behavior has become too difficult to safely manage at home. Pierri is medical director of the Merck Inpatient Unit, an acute care psychiatric facility. His team’s primary goals are to adjust medications, identify potential triggers of behavioral problems and improve patient and family safety after discharge.

When the Merck unit opened its doors in 1974, it was the only specialized inpatient unit for people with autism in the United States. More than 40 years later, only a handful of such units exist across the country. Part of what continues to make Pitt’s unit unique is its commitment to helping affected individuals across the life span.

Continue reading about the unit and promising research to help families in Pitt Med magazine.