Subscribe to Pittwire Today

Get the most interesting and important stories from the University of Pittsburgh.Meet Ella P. Stewart, the first Black woman to graduate from Pitt's pharmacy school

The following article, written by E.R. Shipp, was originally published in Blue Gold and Black, 2010

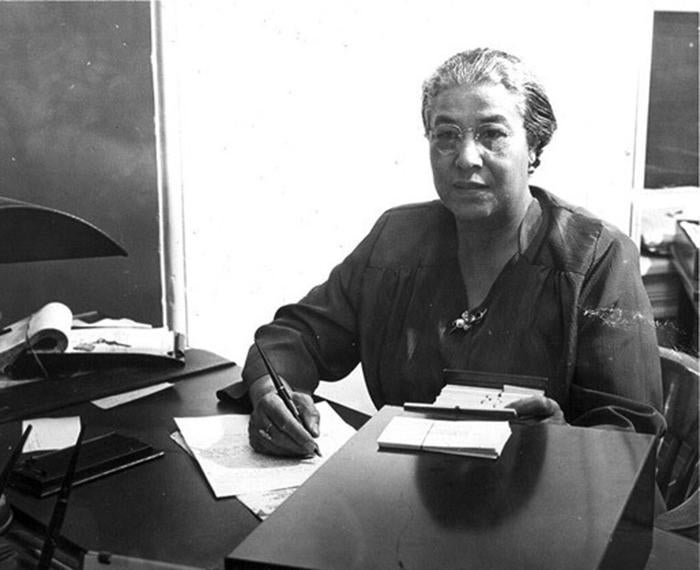

When Ella P. Stewart was recognized as a recipient of the University of Pittsburgh’s Distinguished Alumnus Award in 1969, she and the University had come a long way since 1914, when the then 21-year-old was admitted to Pitt’s School of Pharmacy in an atmosphere that was anything but all-embracing to Black women. The official letter informing Stewart of the honor concluded, “Ella P. Stewart fought her entire life against the barriers of racism and triumphed over them with great dignity and an effortless grace.”

When she died on November 27, 1987, in Toledo, Ohio, Stewart was described in The Toledo Blade newspaper as “one of Toledo’s distinguished citizens, but her renown spread throughout the United States and abroad.” The obituary went on to note, “Before she came to Toledo, however, Mrs. Stewart attained distinction as the first Black woman to be graduated from the University of Pittsburgh School of Pharmacy; and in 1959 she became the first woman to receive a plaque from that institution for outstanding contributions to pharmacy.”

This pioneer, not just in the field of pharmacy but also in the field of international women’s rights, was born in West Virginia. She began her career in Pennsylvania, lived in Ohio for more than 60 years, and is still recognized at Pitt in the form of a scholarship endowed in the Department of Biological Sciences. Her accomplishments are further remembered through collections of her papers and artifacts at Bowling Green State University (BGSU) and the University of Toledo.

Ann Bowers, an archivist at BGSU who worked with Stewart on assembling her collection and who lunched with her on a regular basis in the last years of her life, said Stewart “was the most gracious woman who up until the day she died fought for equality and civil rights.” In the last decade of her life, for instance, an octogenarian Stewart challenged racial barriers that prevented Blacks from being admitted to an assisted-living community in Toledo. She won.

As should be apparent, Stewart offered so much more than the advertised fare of Stewarts’ Pharmacy, which opened in 1922. Ella and Doc Stewart’s apartment above the drugstore served as a meeting place for civic leaders hashing out Toledo’s problems. It also was a guesthouse for Black luminaries like jazz musician Art Tatum who were barred from the best hotels because of their race.

Shirley L. Green, who was charged with the task of digitalizing Stewart’s BGSU collection, says Stewart stood as a silent contributor in the early stages of the Civil Rights Movement, but her contributions were great and many. “The fact that she was a player on the national stage, along with heavyweights like Mary McLeod Bethune, Mary Church Terrell, et al., is pretty amazing.”

Indeed, like Mary McLeod Bethune and others, Stewart was a major contributor to social activism in her time. In 1948, she was elected to a four-year term as president of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs, Inc. (NACWC), and later served as a delegate of the NACWC at the International Council of Women of the World in Athens, Greece. She has been honored with coveted community service awards and inducted into the Ohio Women’s Hall of Fame. And this illustrious professional career of civil service all started at the University of Pittsburgh.

In the early 1900s, Blacks at Pitt were few and far between, and Mrs. Charles Myers — as Stewart was known in her Pitt years, reflecting the name of her first husband—was initially told there was no room for her in the pharmacy school. However, having endured many challenges, including the death of a young daughter due to whooping cough, she persisted and was admitted to a very segregated setting.

In the classroom, White males had the first rows of seats, and they were followed, in descending order, by White females, then Jews, then Blacks. Blacks and Jews often worked together to obtain what was left of textbooks and other resources. And in 1916, as the introduction to her collection at BGSU notes, Mrs. Charles Myers “graduated with high marks, passing her state exam in 1916 to become the first licensed African American female pharmacist in Pennsylvania and one of the earliest practicing African American female pharmacists in the country.”

Sadie Gee is not surprised by her aunt’s tenaciousness.

Gee, a retired operating room nurse, says, “The key thing in our family was education. Ever since anybody could remember, they were told that with an education you could grow and make your way in the world. Everybody believed that if you got a good education, you were more free.”

Gee recalls Stewart preaching the same message to the younger generations of the immediate family. Gee remembers Stewart having a certain determination about her. She says, “She went by the rules, but she pushed and pushed and pushed — but politely.”

Pushing on a larger-than-life stage, Stewart promoted interracial understanding, engaged in charitable efforts, and traveled far and wide on behalf of women’s clubs and other national organizations. The collections at the University of Toledo and BGSU include letters and certificates concerning her appointments to, among others, the National Advisory Committee on the White House Committee on Aging, the Women’s Advisory Committee on U.S. Defense Manpower by the U.S. Department of Labor, and the Executive Board of the U.S. Commission of United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), and goodwill ambassador for the U.S. Department of State. As an ambassador, she toured more than 20 nations, lecturing in such countries as India, Indonesia, Japan, and China.

She figured prominently in the news media, including several articles in The New York Times and The Blade and at least one in Time magazine because of a particularly ugly racial incident.

In early 1957, Virginia Gov. Thomas B. Stanley and the state’s Chamber of Commerce sent out more than 200 engraved invitations for a dinner that would honor distinguished sons and daughters of the “Old Dominion” who had moved to other states. The year 1957 marked the 350th anniversary of the founding of Jamestown, the first permanent European settlement in the United States.

The names of the invitees, apparently taken from various sources, inadvertently included seven Blacks. Described as “an arch-foe of integration,” the governor ordered the recision of the invitations to Stewart and others, including Clilan B. Powell — just back from a history-making celebration of Ghana’s independence from Great Britain. Telegrams were sent out disinviting them. Powell hinted that he might attend anyway, but Stewart made it clear that she had no intention of permitting the state of Virginia to embarrass her.

In case some of the more unpredictable Blacks — like Powell, the publisher of New York’s Amsterdam News — showed up, a table was set in the balcony near the staircase, and Blacks were to be directed there. None of them appeared. According to Bowers of BGSU, Stewart responded to the disinvitation with a letter to the governor and the Chamber of Commerce, saying, “Well, I won’t come, but I still have officially accepted your honor and that honor is still mine.” The Blade reported that in keeping the invitation — part of the BGSU collection — she hoped to be able to show it to a younger generation “and say that Virginia has had ‘a change of heart.’ ”

May 17, 1957, marked the third anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark decision on Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, but in Toledo, Stewart was the center of attention. At the exact time that some 125 whites were being honored by Gov. Stanley in Virginia, Stewart was solely honored as a Distinguished American at a dinner that provided interracial testimony to her achievements. The event was sponsored by officials in Toledo in direct response to Virginia’s race-based slight of Stewart’s accomplishments. The Toledo Bronze Raven, Toledo’s weekly African American newspaper at the time, editorialized that such a local tribute was long overdue. It noted, “Mrs. Stewart is a citizen of the world.”

Ella Nora Phillips, born March 6, 1893, in Stringtown, West Virginia, was the daughter of Hampton and Eliza Phillips. Hampton’s father was Native American and White; Eliza’s parents were Black.

Hampton was a farmer — a sharecropper most likely — and Eliza was a homemaker overseeing a house that included five other children: Walker, Charles, Henry, Bowles, and Hattie. Stewart received her early education at Storer Normal School (later Storer College), located near Harpers Ferry in West Virginia. In this place, where Stewart was being nurtured to become a teacher to advance the race, she fell in love with a classmate, Charles Augustus Myers.

On her way north for an advanced teaching degree, she disembarked from a train in Pittsburgh and married Myers in 1910. Because of that decision, she and her father were estranged for several years.

Charles Myers worked as a chauffeur, one of the more prized jobs for Black men in Pittsburgh. Ella was a homemaker, but when the Myers’ only child, Virginia, died of whooping cough, it sent Ella into a tailspin and spurred her friends to encourage her to find something to do outside the house.

While working as a bookkeeper in a pharmacy, she decided to resume her education at the University of Pittsburgh.

After graduation and the end of her first marriage in divorce, she operated two pharmacies in Braddock, Pa., for a number of years. When that proved to be too much, she moved back to Pittsburgh in 1919 and opened another pharmacy. But later that year, an illness necessitated that she move back to her parents’ home in Virginia; she asked a fellow African American Pitt pharmacy alumnus, William Wyatt “Doc” Stewart, Class of 1914, to fill in for her. In 1920, sometime after her return, she and Doc were married.

They were fairly peripatetic, it seems, in those early days, with a move first to Youngstown, Ohio, where Stewart broke the color barrier and became the druggist at the Youngstown City Hospital, and then it was on to Detroit. After learning that there was no Black pharmacy in Toledo, the Stewarts bought a building there, established their business on the street level, and transformed the upper floor into a residence. They closed the drugstore in 1945, perhaps because of Doc’s health and perhaps because of her growing activities beyond the business.

A teacher at the Ella P. Stewart Academy for Girls, Cecilia Ragans, told The Blade earlier this year that when she was growing up, the pharmacy was a neighborhood hangout for teenagers, but Stewart permitted only two kids to enter at a time. She also recalls how Stewart often urged them to be proud and to hold their heads up high.

Gee, who lives in Reedville, Virginia, told The Blade, “She was a kind and generous, but firm lady. She was a stickler for protocol and decorum and all the things people did in those days.”

In her obituary, The Blade noted that of all the awards and citations she received from local, national, and international organizations, “Mrs. Stewart seemed to cherish most deeply the naming of an elementary school in her honor in 1961.”

Apparently, The Toledo Bronze Raven was a primary leader in the drive to name the new elementary school for Stewart. The weekly newspaper was joined by a school board member, Frank A. Brown, who suggested a choice between George Washington Carver, the renowned scientist with no Toledo connection, and Stewart.

In August 1960, The Toledo Bronze Raven editorialized: “What we would like to see is something that will symbolize our accomplishments in Toledo. It seems to us that no one will begrudge such an honor to Mrs. Stewart, who has given so unselfishly of her time to various causes.”

She often visited with teachers and students, especially on her birthday, which was a celebrated occasion at the school.

“I never dreamed I’d have anything named after me,” Stewart told The Blade in 1985.

In 2003, the school became the Ella P. Stewart Academy for Girls. In 2009, a museum dedicated to her opened at the school, and her niece, Sadie Gee, attended the ceremony.

When she paused in her travels, Stewart would sometimes stay with Gee’s family in the Washington, D.C., area. Gee looked forward to visits from her Aunt Ella, who served as an envoy for education in different countries. Stewart traveled throughout North and South America and Europe and, in one memorable four-month trip, went to Pakistan, India, Sri Lanka (then Ceylon), Indonesia, Japan, Hong Kong, and the Philippines.

Gee recalled a time when her aunt showed her a box filled with rubies, pearls, emeralds, and diamonds — gifts from people she had met abroad. Gee also remembers a piece of advice: “You be decent and nice to people when you are on your way up, because you may pass those people on the way down.”

A few years after Doc Stewart died in 1976, Ella Stewart sought to move into an assisted-living community in Toledo but was denied admittance. She politely but firmly reminded the administrator that the residence had received federal funding that prohibited racial discrimination. She was soon admitted and was particularly proud when more Blacks moved in after her.

After her death in 1987, her estate awarded to Pitt, via its Department of Biological Sciences, an endowment to reward a student at the beginning of his or her sophomore year for first-year excellence. In a departmental convocation in the fall term, students are told: “The endowment for this award was left to the department by the estate of Ella P. Stewart, Class of 1916, to be used toward an annual prize of a book store certificate by a deserving first-year student.”

Stewart would no doubt be proud. The inscription underneath her photo in the 1916 University yearbook, The Owl, says: “Can be distinguished by her wisdom. It would seem as if she could succeed in about anything undertaken, as there isn’t a single study which seems to mystify her. She has the wishes of the entire crew for her success.”

Photographs courtesy of the Bowling Green State University Libraries