Subscribe to Pittwire Today

Get the most interesting and important stories from the University of Pittsburgh.Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, along with displacing millions, has reportedly risked several nuclear incidents. Soldiers shelled and captured Europe’s largest nuclear power plant and, more recently, a power outage at the Russian-occupied Chernobyl power plant has raised the possibility of nuclear leakage.

In this 2020 story from Pitt’s Innovation Institute, two researchers discuss their genetic test that has eliminated thousands of unneeded surgeries for thyroid cancer — a disease they became intimately familiar with living in Minsk, Belarus, less than 200 miles from the 1986 site of the world’s worst nuclear disaster.

The thyroid sits just below the Adam’s apple. Shaped like a butterfly, its two lobes wrap around the windpipe connected by a narrow isthmus. The hormones it produces regulate everything from metabolism and body temperature to growth and brain development.

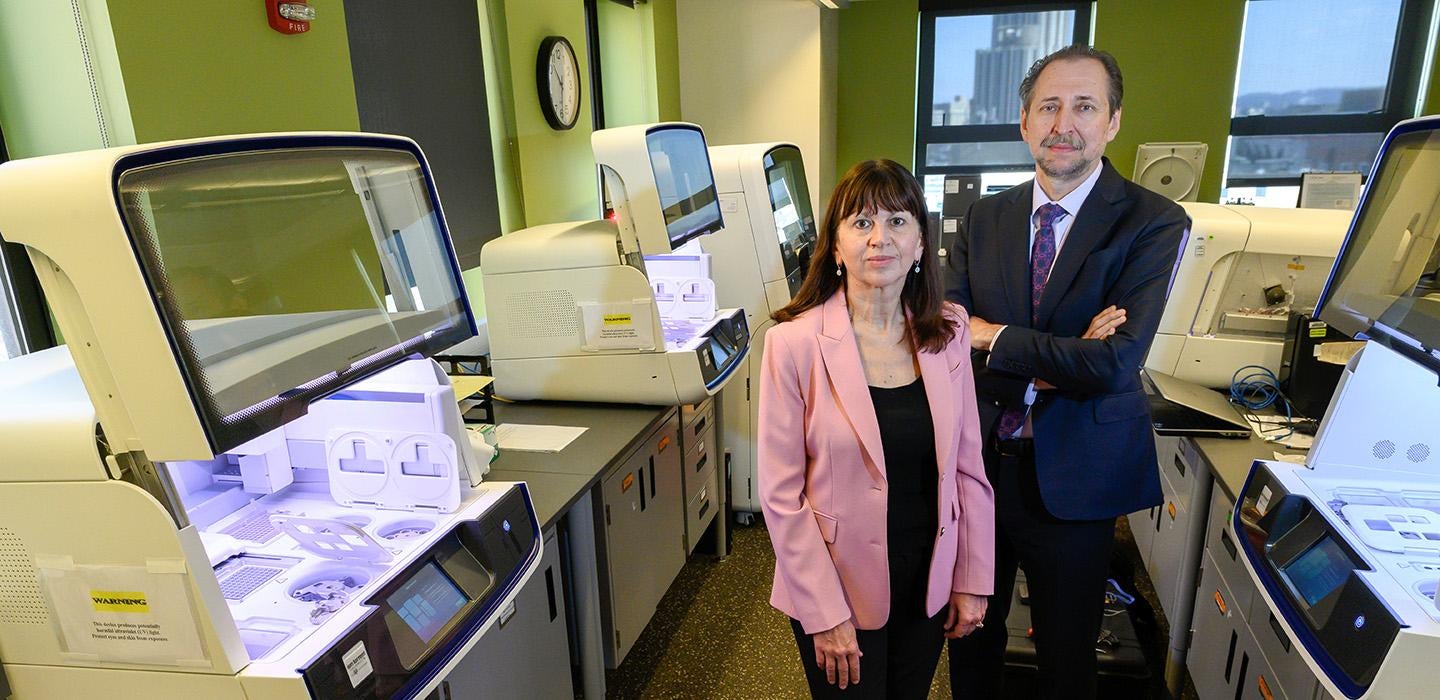

This unheralded yet vital gland is a metaphor for the work of Yuri Nikiforov and Marina Nikiforova, who respectively are the vice chair of the Department of Pathology and director of the Division of Molecular Pathology at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine and the Director of the Molecular and Genomic Pathology Laboratory at UPMC.

The husband-and-wife team credit the two co-equal “lobes” of their work with allowing them to develop a diagnostic test for thyroid cancer that is helping to eliminate thousands of unnecessary thyroid removal surgeries, benefiting people who otherwise might face a diminished quality of life and lifelong hormone-replacement therapy.

On one side is the research lobe through the university, and on the other is the clinical lobe through UPMC. Uniting these two pieces is their laboratory, which has gone from running about 500 cases per year through their gene sequencing machines when they first arrived in Pittsburgh in 2006, to more than 30,000 cases per year today, and growing. If a biopsy is done to screen for cancer in UPMC’s health network, odds are it goes through the Molecular and Genomic Pathology lab for sequencing. And in an age when more and more genetic biomarkers for cancer are being uncovered and treatments targeted to specific biomarkers are being developed, the analysis the lab provides is helping to fine-tune cancer prognosis and point the way to more effective treatment.

It was the unique environment and resources afforded by the marriage of their research and clinical roles at Pitt and UPMC, they say, that made it possible for them to develop, test and improve their thyroid cancer test to the point where it was ready for licensing and distribution, without requiring a significant external investment.

“To be able to clinically validate the test on a large number of patients in a single location is not something you can do in very many places,” Nikiforova said.

They named the test ThyroSeq (pronounced THY-RO-SEEK), themselves, and Nikiforova created the illustration for the logo.

UPMC licensed ThyroSeq from the University in 2017 and partnered with CBLPath, Inc., a branch of the Austin, Texas-based Sonic Healthcare USA, to distribute it beyond UPMC’s network of physicians and hospitals. ThyroSeq, in a few short years, has become one of the most successful licenses in the university’s history, both in terms of commercial success and, more importantly, on the impact it is having on people.

Thyroid nodule biopsies from around the nation and from several countries around the world now pour into the lab for analysis.

With their experience with thyroid genetics and test composition at a mature stage, Yuri and Marina are working with their colleagues at UPMC to expand the use of genetic information generated by this test to help patients with cancerous nodules to decide on the optimal extent of thyroid surgery.

Yuri and Marina said the guidance they have received from the Innovation Institute has been invaluable in allowing them to pursue commercialization of the test while not losing focus on the lab’s research and operational mission.

“We are grateful to (senior licensing manager) Maria Vanegas for her belief in the product and the advice and support she has provided from the very beginning and through the licensing process,” Yuri said.

Vanegas, for her part, said it has been a pleasure working with scientists who frame their work on how it can translate from the lab to the market and make an impact on people’s lives.

“The symbiotic relationship between Pitt and UPMC affords our researchers the opportunity to have access to large patient pools, which allows for the unmatched opportunity to accelerate the development of diagnostic assays such as ThyroSeq,” she said. “I am excited for the new opportunities they are pursuing for diagnosing certain other types of cancer.”

Nikiforov’s window into molecular genetic pathology of the thyroid is no accident, but it is directly related to a very big accident. The couple hails from Minsk, Belarus, the capital of a former Soviet republic. Minsk is situated less than 200 miles from Chernobyl, the Ukrainian town that experienced the world’s worst nuclear power plant disaster in 1986. The massive explosion and meltdown released radioactive material into the air, causing increased incidences of thyroid cancer, particularly among young children, across a wide radius.

He was a pathology resident at the time and ever since has focused his research on the genetics and pathology of thyroid cancer.

Just as he was able to prove then that the Chernobyl accident was affecting public health, Yuri, alongside Marina, continues to seek new discoveries that unlock genetic clues to when and how to treat cancer.

Nikiforov noted that global progress in identifying new genetic markers of cancer, combined with the increased capacity and computing power to test for those markers in gene sequencing machines, have created a foundation for developing cutting-edge molecular tests for cancer that only require a small number of cells for analysis.

The genomic pathology lab is a convener of a multi-disciplinary group of Pitt/UPMC surgeons, oncologists, pathologists and endocrinologists that regularly put their heads together to share expertise to design new trials or tailor clinical therapies for patients.

While he is thrilled with the commercial success of the ThyroSeq test, Nikiforov’s primary motivation is still driven by his love of science.

“For me, the science and discovery is the most important part,” he said.

But when discovery leads to a product that makes a tangible impact on society, it makes the whole process even more exhilarating.

— Mike Yeomans