Subscribe to Pittwire Today

Get the most interesting and important stories from the University of Pittsburgh.Cathedral of Learning or Cathy? Explaining the debate over Pitt's most iconic building

There’s a language debate that’s been roiling the University of Pittsburgh community in recent years. It’s a controversy that strikes at questions of tradition and evolution, convention and colloquialism.

When referring to the revered Gothic revival edifice at the heart of the Pittsburgh campus, what do you call it? The Cathedral of Learning? The Cathedral? Or Cathy?

Not all members of the Pitt community participate in these verbal polemics, but those who do tend to have strong opinions. And, given the history and largesse of this iconic monument, Pitt experts say this fervor is justified.

» Voting and T-shirt requests have closed, but check back for additional opportunities to express your love of The Cathedral of Learning. Or Cathy.

First, some history

The beloved structure was named “The Cathedral of Learning” before a single brick was laid. But even at the moniker's inception in the 1920s, not everyone was an immediate fan.

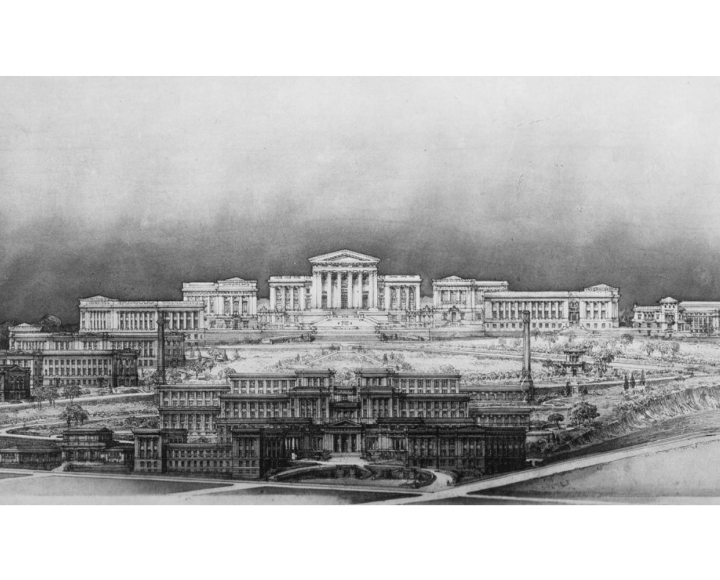

When Pitt first moved to the Oakland neighborhood, the vision for the University campus was more Acropolis-like, a city on the hill with buildings in the neoclassical style, as had been done on campuses like the University of Virginia or Columbia University. It was John Gabbert Bowman, Pitt’s chancellor from 1921 to 1945, who pivoted instead to constructing a central skyscraper, one that would give the growing institution classroom space for its returning veteran students.

Bowman himself wasn’t a big fan of the name. He was, however, savvy and ambitious. He understood the symbolic power of the title, which evoked its lofty aspirations and potential as a functional monument to knowledge: “They shall find wisdom here and faith — in steel and stone, in character and thought — they shall find beauty, adventure, and moments of high victory,” Bowman said.

As the skyscraper took shape, “The Cathedral of Learning” title took hold.

Alumnus Robert Lavelle recalled debating the nomenclature as a child. “If it’s a cathedral, why doesn’t it have a steeple?” His teachers told him because “there is no peak to learning … it’s a lifelong process, and that’s why the architects had to leave the top open.’”

This high-flown rhetoric, tying the steel industry to a historic and prestigious building project, had strategic marketing value given that Bowman sought to raise $10 million from the public to finance the structure.

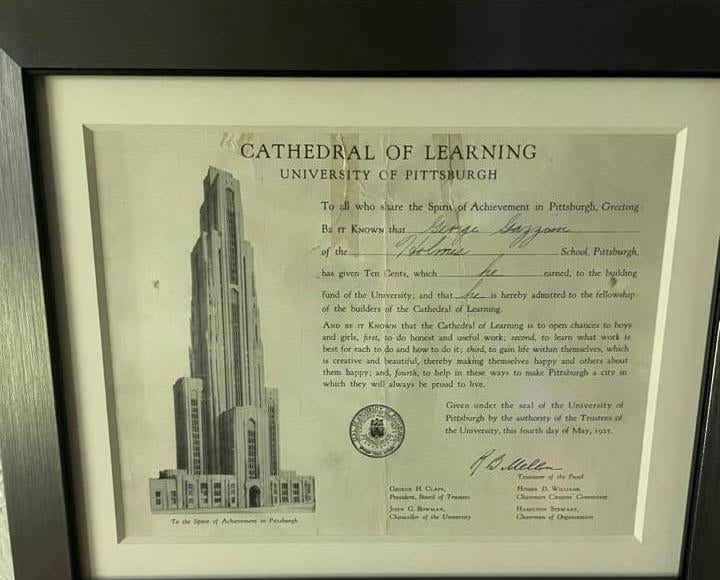

Enter here the dimes of 97,000 Pittsburgh schoolchildren, whose families participated in the “Buy a Brick Campaign.” Many Pittsburghers still prize the certificates they or their families received in exchange for the coin that admitted them “to the fellowship of the builders of the Cathedral of Learning.” The promise of the builder certificates shows that collective ownership was a central part of the story of the monument from the first. Each certificate reads:

“The Cathedral of Learning is open to boys and girls, first to do honest and useful work; second to learn what work is best for each to do and how to do it, third to gain life within themselves, which is creative and beautiful, thereby making themselves happy and others about them happy; and fourth, to help in these ways to make Pittsburgh a city in which they will always be proud to live.”

An evolving cathedral

In the words of visionary architect Frank Lloyd Wright, whose Fallingwater house is situated 60 miles southeast of Pittsburgh, “We create our buildings and then they create us.” (For the record: Wright was not a fan of The Cathedral of Learning’s design, and said, “If this is the best learning can do, let’s get unlearned.” Rude.)

Built environments are co-created every day, over the course of years. This helps explain why those who spend time in and around certain buildings, who look at them from their windows or on their daily commutes, feel an affinity for them.

Pitt History of Art and Architecture Professor Thomas J. Morton has spoken to his classes about the place The Cathedral holds in the Pitt collective conscious.

“Here is a building that transcends its own specific place within the University,” Morton said, adding that it is not merely a University building, it’s a Pittsburgh landmark.

How such landmarks are used, what they symbolize and what they’re called shifts over time. “Building is dynamic. It has to change. Even the shape of The Cathedral has entered into the popular lexicon of the University,” Morton said, pointing out that the building influenced the redesign of Pitt’s football jerseys.

[This senior’s love song to The Cathedral of Learning struck a chord]

Just as Pitt’s spirit colors can change, how we talk about the University experience also changes. Sometimes that is a top-down evolution, other times it comes from the bottom up.

Young people are often the progenitors of lexical changes, said linguistics Associate Professor Abdesalam Soudi. Younger people are creative with language and flexible, adapting easily and adopting new terms fluidly.

Regardless of who initiates linguistics shifts, the change is not random. Soudi said the creation of “Cathy” follows its own grammar, through what’s known as a productive morphological process.

And “Cathy” for The Cathedral of Learning is an example of a specific kind of truncation called back-clipping.

“An example of that is our chancellor: he goes by Pat. Patrick, Pat,” Soudi said. Sometimes these clippings of names become names in their own right. People generally like using shortened words and names because they’re easier to write and speak.

Whatever the neologistic process, The Cathedral of Learning is just one of dozens of landmark buildings to experience a name evolution. The Fuller Building in New York is now known as The Flatiron Building, while London’s Leadenhall building is now colloquially called The Cheese Grater. When The Empire State building first opened in 1931, it was nicknamed the “Empty State Building,” as only a small percentage of its space was rented. Renzo Piano may not have wanted to call his recent London building The Shard, when the public offered the name, he adopted it.

A generational divide?

For Professor Soudi, the Cathy or Cathedral debate is a timely and fun example through which to talk about sociolinguistics and the power of language.

“Language is found in every aspect of our human experience and existence, and it obviously affects and influences how we and others perceive the world and perceive each other,” Soudi said.

Just as language is not static, our identities are also changing and evolving. And the two are intimately connected, he said. “We transmit and express our identity through language and that’s a salient way, or really one of the central ways, to mark our group identity and membership.”

For college students who are entering a new community, language is a big part of marking your place in a new space and indicating that you belong and expressing who you are.

It is almost universally agreed that the Cathy/Cathedral divide is generational, but it is difficult to say where the boundary lies.

The nickname “Cathy” seems to have been popularized in the early 2010s and has grown steadily more popular in the past few years. Now, it is the default term for the building for many current Pitt students.

While the popularization of “Cathy” is almost definitely in part an expression of recent students’ less formal approach, it might also have something to do with the student experience in recent years.

Morton told a story about a standout student who shared that losing access to the building during COVID-19 closures actively hindered his academic achievement.

“Right now, situationally, historically, in the midst of the pandemic, there’s a comfort level of calling it Cathy,” Morton said.

The shortened term with its –y suffix is a diminutive, or what some linguists call “hypocorism,” Soudi said. Though the words sound alike, a diminutive doesn’t mean diminishing, rather it expresses intimacy and affection for something.

“It’s a lexical expression of fondness,” Soudi said.

[Photos: Students make a sweet rendering of a gingerbread Cathedral of Learning]

That said, previous students — now alumni — also marked their status as Pitt students through language, including calling it The Cathedral.

“If people are using this word to negotiate membership and marking solidarity with others, by asking them to drop that lexical variant you’re asking them to drop all these things,” Soudi said. “You’re asking them to drop who they are.”

Morton noted a connection to how other types of formal titles have also evolved. Students and professors have dropped formal titles for one another in more settings. Some professors include notes in their syllabi to call them by their name. His own students call him by his initials, TJM.

“Do they respect a professor less if they refer to him or her or them by their first name? I would bet a dozen donuts that it doesn’t change their level of respect,” he said.

Words matter

In an era of rapidly shifting cultural norms, technological change and divisive political rhetoric, most would agree the fight over “Cathy” is not the most urgent subject of debate. Ultimately, all are united by their love and respect for the building and the “moments of high victory” it symbolizes.

But just because something is “objectively silly,” said alum Morgan Flood, “doesn’t mean that it doesn’t have meaning."

“Looking at something that’s objectively fluffy still tells you something that’s valuable and interesting,” Flood added.

For Morton, what students’ opinions about “Cathy” convey is that the building is enduring, and — from an architectural standpoint — a success. “I love the fact that they have such an attachment to a building on campus. I think it’s more important that people have this connection, than whether you call it Cathy or The Cathedral."

IN THEIR OWN WORDS: Team Cathedral

- “I see her every day. I think she’s a beacon of respect for the University and the city. She’s kind of like a queen of Oakland. I understand that the times change, but I also feel like you wouldn’t call Queen Elizabeth, Becky or Beth. The Cathedral garners the same respect.”— Jen Weidenhof (A&S ’92)

- “We’re fortunate to have a beautiful building like that, I agree that the formal version connotes respect. It’s almost like you’re getting too personal. Not only are you being flippant, you’re calling it a person’s name, a woman’s name or a man’s name. My oldest sister is named Cathy and even she agreed, don’t call it that.” — Andy Zarroli, Pitt fan, Dietrich student in the 1980s

IN THEIR OWN WORDS: Team Cathy

- “It was a thing when I was a freshman. I remember people calling The Cathedral ‘Cathy’ and initially being like, ‘hmmm, I don’t know about this.’ Cathy feels right to me now. I know there are some older folks that find it disrespectful, but it’s affectionate, it’s showing investment and fondness more than anything else. Formality doesn’t have to indicate respect and vice versa.” — Morgan Flood (A&S ’17)

- “I love the nickname Cathy! It makes me feel like I’m more connected to the school, and I think it shows how much the community loves the building. She’s such an iconic part of Pitt, she deserves a nickname!” — Sahil Khattar, A&S student

— Acacia O’Connor