| front |1 |2 |3 |4 |5 |6 |7 |8 |9 |10 |11 |12 |13 |14 |15 |16 |17 |18 |19 |20 |21 |22 |23 |24 |25 |26 |27 |28 |29 |30 |31 |32 |33 |review |

|

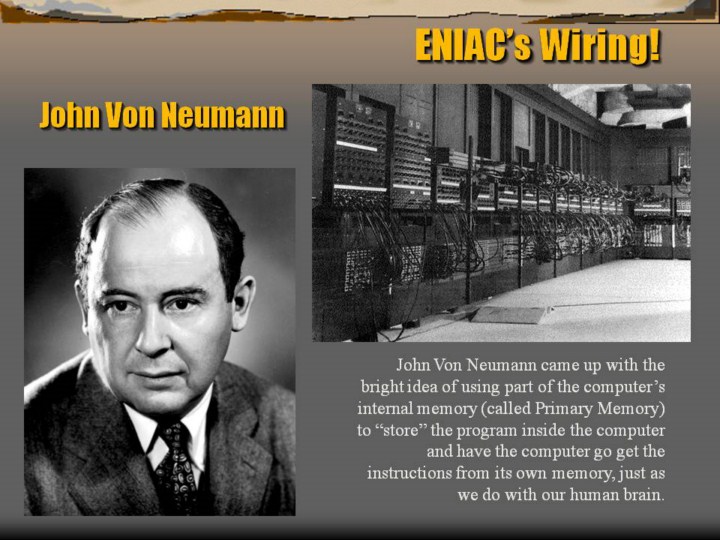

Like all the earliest electronic digital computers, the ENIAC was programmed manually; that is to say, the programmers wrote the programs out on paper, then literally set the program for the computer to perform by rewiring it or hard-wiring it—plugging and unplugging the wires on the outside of the machine. Hence all those external wires in the picture above and on the previous slide.

Then along came John Von Neumann, who worked at Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study and who collaborated with Eckert and Mauchly. He came up with the bright idea of using part of the computer’s internal memory (called Primary Memory) to “store” the program inside the computer and have the computer go get the instructions from its own memory, just as we do with our human brain. Neato! No more intricate, complex, cumbersome external wiring. Much faster; much more efficient.

Unfortunately, it didn’t solve the problem of the possibility of error. As long as humans are around, we’ll always have that!

It’s iroonic that Eckert and Mauchly were upset when Von Neumann was given credit for this “stored program concept,” because they thought they deserved it, too. Now why didn’t they think the same about Atanasoff? Go figure! |