| front |1 |2 |3 |4 |5 |6 |7 |8 |9 |10 |11 |12 |13 |14 |15 |16 |17 |18 |19 |20 |21 |22 |23 |24 |25 |26 |27 |28 |29 |30 |31 |32 |33 |34 |35 |36 |37 |38 |39 |40 |41 |42 |43 |44 |review |

|

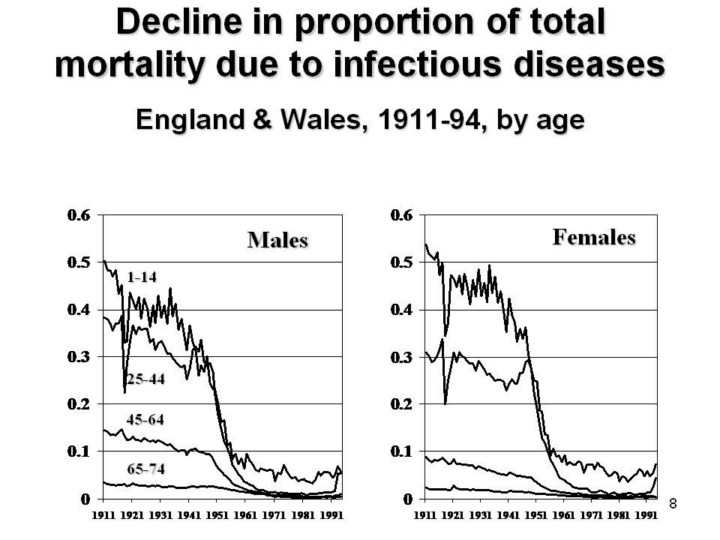

Here we see the decline over time in the proportion of mortality at different ages attributable to infections ranging from tuberculosis to diuphtheria, measles and gastro-intestinal infections. The downward spike in 1918 is because most excess deaths were from pneumonia rather than “influenza”. Rates of pneumonia were much lower than those for infectious diseases either side of the 1918 Spanish flu – making up less than 10% of all deaths among those aged The sharp decline mid-century is not well understood and is under-researched. The precise role of the introduction and use of anti-biotics is important question.. Mackenbach’s work suggesting that this played a role in the Netherlands at least. With the decline of infectious diseases life-expectancy in particular becomes more strongly related to the influence of individual behaviours. This is apparent with the widening gap in male to female life-expectancy over the 20th Century which rose from 4 years in 1900 to a peak of just over 6 years in the late 1960s.

|