| front |1 |2 |3 |4 |5 |6 |7 |8 |9 |10 |11 |12 |13 |14 |15 |16 |17 |18 |review |

|

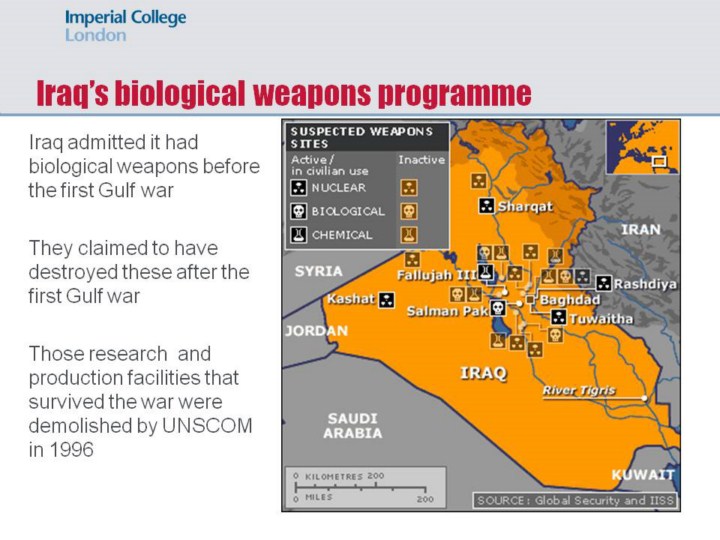

Saddam Hussein’s Iraqi regime had admitted to developing an offensive biological weapons programme before the start of the first Gulf war, including bombs filled with botulinium toxin and anthrax spores, and prototype spray tanks capable of being mounted on remotely piloted aircraft (Danzig & Berkowsky, 1999). After its invasion of Kuwait in August 1990, Iraq engaged in what it called a ‘crash programme’ to produce large amounts of biological weapons (Stern, 1999).

In preparation for the first Gulf War, US troops were immunized against anthrax and botulinum and soldiers were issued with a five-day course of ciprofloxacin. Some 60,000 of the 697,000 US troops and 567 of the 45,000 UK troops who served in the first Gulf War complained that they developed so-called Gulf War Syndrome, (also known as ‘Saudi flu’ or ‘desert fever’). Iraq’s admission that they had biological weapons, added to the suspicions that Gulf War Syndrome was caused by either a toxic agent, or by the vaccines given, or a combination of both. Medical researchers investigated an infectious cause for the phenomenon, particularly as some family members of soldiers who had not been to the Gulf also reported symptoms, but the US Defense Department found no clear cut evidence of transmission. Mainstream medical opinion believes that Gulf War Syndrome was the product of combat stress, which was physically and mentally acute in the Gulf war (Showalter, 1997).

After its defeat in February 1991, the Iraq government claimed to have destroyed its biological arsenal. Research and production facilities that escaped destruction during the war were demolished by the United Nations Special Commission on Iraq (UNSCOM) in 1996 (Danzig & Berkowsky, 1999). Iraq was then subject to multiple intrusive inspections by UNSCOM. Yet ‘[e]ven with unrestricted access and a broad range of on-site measures, inspectors failed to uncover any unambiguous evidence of illicit biological weapons activity’ (Kadlec et al., 1999): 96). |