Search for most updated materials ↑

| front |1 |2 |3 |4 |5 |6 |7 |8 |9 |10 |11 |12 |13 |14 |15 |16 |17 |18 |19 |20 |21 |22 |23 |24 |25 |26 |27 |28 |29 |30 |31 |32 |33 |review |

|

Constructed by GHN Supercourse group

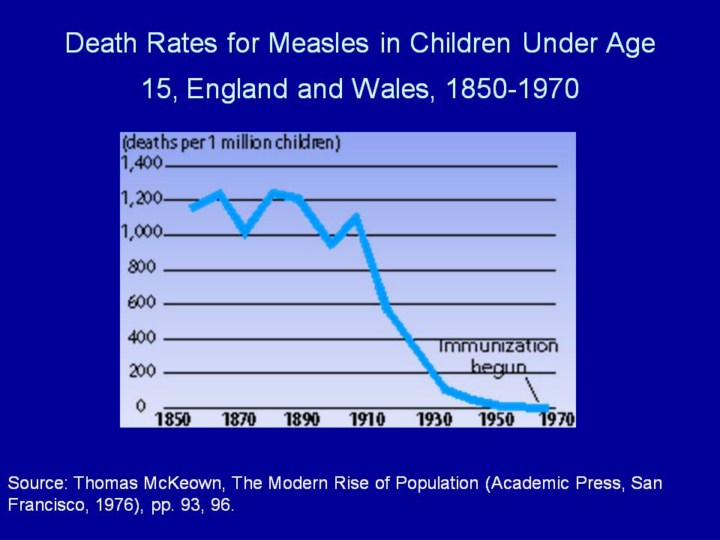

Epidemiologic Transition and Health Today, it is widely assumed that with increasing economic growth, the developing countries will follow the same path as Europe and North America and experience what has become known as the "epidemiologic transition." This term describes the changing patterns of disease that accompanied overall improvements in health in the late 19th and early 20th Century. As mortality rates declined and life expectancy rose, these populations experienced a shift in the pattern of disease, from one dominated by infectious diseases to one dominated by chronic disorders such as heart disease and cancer. The shift to chronic diseases can be partly explained by the fact that many more people were living to the age when chronic diseases strike. Even so, this transition represented not just a simple substitution of one set of problems for another but an overall improvement in health. Elements of this epidemiologic transition are in fact occurring now, to varying degrees, throughout much of the developing world. In some of the middle-income countries of Latin America and Asia, for instance, chronic diseases now take as great or an even greater toll than infectious diseases [1]. But this transition is by no means complete. Many countries, especially the poorest, still have a huge burden of infectious diseases along with a growing problem of chronic diseases. These populations have not traded one set of problems for another; instead, they are suffering from both, in what is known as the "double burden" of disease [2]. Nor is the transition inevitable. As the history of the Sanitary Revolution illustrates, concerted policies and investments are necessary to improve both environmental quality and public health. 1. Christopher J. L. Murray and Alan D. Lopez, eds., The Global Burden of Disease: Volume 1 (World Health Organization, Harvard School of Public Health, and The World Bank, Geneva, 1996), p. 18. 2. A. Rossi-Espagnet, G.B. Goldstein, and I. Tabibzadeh, "Urbanization and Health in Developing Countries: A Challenge for Health for All," World Health Statistics Quarterly, Vol. 44, No. 4 (1991), p. 208. |