Search for most updated materials ↑

| front |1 |2 |3 |4 |5 |6 |7 |8 |9 |10 |11 |12 |13 |14 |15 |16 |17 |18 |19 |20 |21 |22 |23 |24 |25 |26 |27 |28 |29 |30 |31 |32 |33 |review |

|

Author: John Last, Canada http://www.pitt.edu/~super1/lecture/lec2561/007.htm

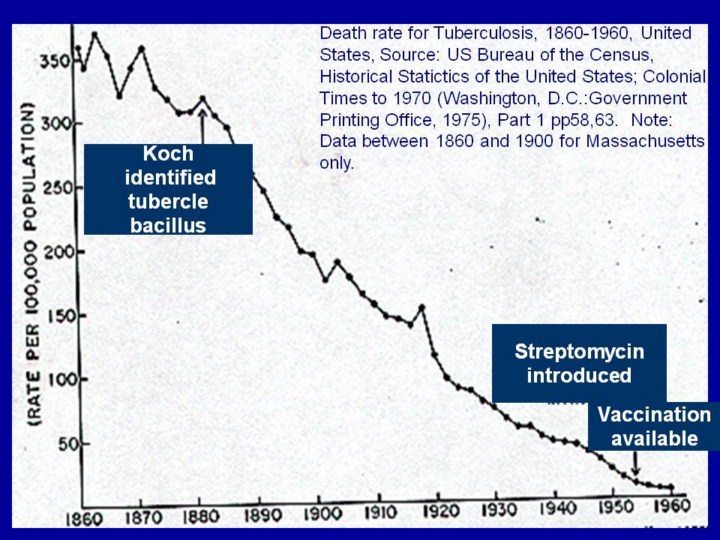

Death rate for Tuberculosis, 1860-1960, United States, Source: US Bureau of

the Census, Historical Statictics of the United States; Colonial Times to

1970 (Washington, D.C.:Government Printing Office, 1975), Part 1 pp58,63.

Note: Data between 1860 and 1900 for Massachusetts only. Ecological

Determinants of Disease The 19th century change in the pattern of disease was more than a direct cause-effect relationship of improved sanitation to reduced death rates from infections, it was aided by a change in values and behavior. The death rate from tuberculosis began to fall in the early 19th century and continued to fall steadily long before the discovery of effective chemoprophylactic regimens virtually wiped out the disease in the rich nations in the 1950s. Prosperity led to improved housing conditions and better nutrition. Literacy increased. It became less common for several children in the family to share the same bed. Being well-fed, better housed, well-informed, and separated from others by enough space to reduce the probability of person-to-person transmission of infection, all helped to reduce the burden of premature death. Perhaps there was also a rise in the natural (maternal to infant) level of immunity to some of the infections that had previously carried off huge numbers of infants and children, and a decline in the virulence of some of the most lethal pathogens. |