| front |1 |2 |3 |4 |5 |6 |7 |8 |9 |10 |11 |12 |13 |14 |15 |16 |17 |18 |19 |20 |21 |review |

|

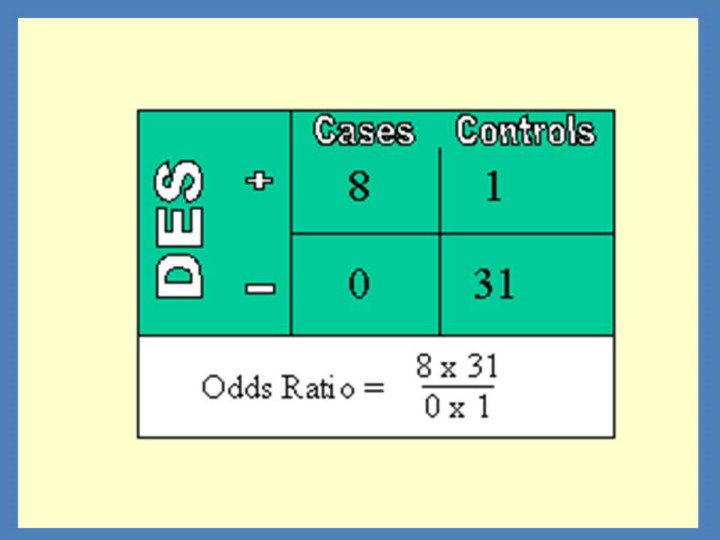

Case control studies, therefore, begin with people with a disease or injury. The next step is to assemble a group of people without the disease who perhaps could have developed the disease, but did not do so (i.e., people of the same sex, same age, more or less, and same general background). The control group should, therefore, be matched to the cases for factors that are not to be studied (age, race, etc), but must not be matched for factors that are to be looked at (this would destroy the study before it began). Case control studies are the only way to go when the disease is rare. One of the classic studies was of eight young women with cancer of the vulva—a very rare cancer at any age—seen in one city in a short period of time. Thirty-two young women were chosen as controls, and both groups were given a series of questions and what finally separated the two groups was a question as to whether their mother had been given DiEthylStilboestrol (DES) pills while the young women were in utero 20 years earlier. The odds ratio was very large indeed. Most studies, however, show smaller differences and therefore used much larger samples to demonstrate statistical significance between the groups; and since the disease is usually uncommon, it is often the case that multiple cities need to cooperate.

|