![]()

home

::: about

::: news

::: links

::: giving

::: contact

![]()

events

::: calendar

::: lunchtime

::: annual

lecture series

::: conferences

![]()

people

::: visiting fellows

::: postdoc fellows

::: resident fellows

::: associates

![]()

joining

::: visiting fellowships

::: postdoc fellowships

::: senior fellowships

::: resident fellowships

::: associateships

![]()

being here

::: visiting

::: the last donut

::: photo album

|

A good experiment ::: More photos Less than four years ago, in October 2010, we held a conference on the philosophy of scientific experimentation. Our sense was that many philosophers of science were thinking about experiments, but they were not meeting face-to-face to share their thoughts. The event itself was an experiment. We--that is Slobodan Perovic, the conference's chair, and I--did not realize how accurate that sense was until the concluding round table discussion. The participants remarked wistfully that this was the only time they had assembled to talk face-to-face. Could they meet again? That question had an obvious answer. It created a conference series. The 2010 conference became "PSX1" and more conferences followed. PSX2 was held in Konstanz the following year, in October 2011. PSX3 was held in Boulder, Colorado, in October 2012. Now we have PSX4.

I still recall that first meeting and my interest in understanding just what issues constituted philosophy of scientific experimentation. They were varied, as I reported in my "donuts" column at the time. http://www.pitt.edu/~pittcntr/Being_here/last_donut/donut_2010-11/10-15-10_experimentation.html There was discussion of the very idea of a philosophy of scientific experimentation and a rather triumphant sense that it had finally matured as a field. Allan Franklin, then our keynote speaker and eminence gris of philosophy of experiment, had listed the tenets of the "new experimentalism." It was by then not so new. Allan quipped that "middle-aged experimentalism" might be the more apt title. There were still mentions by other speakers of the old saw "experiment has a life of its own," but the mentions doubted that experiment could ever really be free of theory.

It now seems that PSX1 was a long time ago. How has the field progressed since that first meeting, I wondered, as the PSX4 participants convened and event started. Is there a sense of community? It was immediately clear that the sense of the community was strong. As the participants strolled in for the first breakfast, they were greeting each other with the familiar conference chatter of nervous participants trying reconnect. "I think we last met at PSX3? Good to see you again!" One speaker introduced her talk with a boast. She was proud that she had finally been accepted as a speaker at a PSX conference. Another was poetically "excited to be invited." How wonderful, I thought. We had worried about whether we could populate the program for PSX1. A place on the program at PSXn is now a coveted honor.

I had seated myself in the far corner of the front row. It is the best place from which to take photos. I had my program at hand to consult as needed and I was watching the time closely. It's what directors of centers do, quietly. Allan Franklin made a few opening remarks and then announced "The chair for this session is Carrie Figdor. . . " Carrie was sitting at the back, an unusual place for a chair. She rose to come forward. It was clear from her hesitations that something was wrong. She leaned over to say something, but didn't. Instead she plucked my carefully folded program from my shirt pocket and went with it to the podium to introduce the speaker. A few moments later, Carrie sat next to me. She leaned over again and pointed at my watch. She then tried to explain in quiet whispers, but even quiet whispers by a chair at the start of a talk are distracting, so she stopped. For the rest of the talk I had a distant view of my program and watch.

Paula Grabowski is an accomplished experimental biologist from the University of Pittsburgh's Department of Biological Sciences. She is our first keynote speaker. She is as much a speaker as a subject of our investigation. For work like hers is what we study. Appropriately, the talk proved to be a semi-autobiographical account of her experimental work. She gave it the appealing, alternative title "23 and me". Non-biologist that I am, I presumed it a nod to the 23 chromosome pairs in a cell nucleus and not to Hilbert's celebrated list of 23 unsolved mathematical problems.

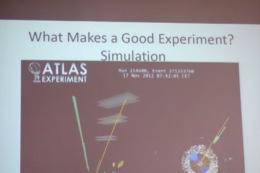

Up came a screen with a familiar term. "A Good Experiment." What makes a good experiment? Paula's slide gave a list of features and she proceeded through them. A good experiment poses a big question, but keeps it simple. It respects evolution, chemistry and physics; there ought to be no violations of the laws of thermodynamics. It exploits genome biology or employs big data. I had a prior reference point for this question. Allan Franklin is our Senior Visiting Scholar this year and the principal conference organizer. He had talked in the lunchtime series, as I reported in an earlier "donuts" page. That answer also agreed with the part of the conference call that elaborated on the question: "In this conference we wish to emphasize answers to the question, "What Makes a Good Experiment?" One can distinguish between conceptually important experiments, those classified by their relation to theory; testing theory, calling for a new theory etc. and technically good experiments, those that measure a quantity of scientific interest with greater accuracy and precision than had been done previously. Both types of experiment must be methodologically good, experiments that give reasoned and valid arguments for the credibility of their results." The agreement with Allan's talk is strong. There's no mystery in that -- Allan wrote the call. Of course, while sitting and listening to Paula speak I couldn't then remember just what was in Allan's list. I had to look it up. But I did retain a sense that Paula's list was different. But what was the difference? Is there anything systematic about the difference? Paula's talk continued. She discussed details of molecular biology that are elementary commonplaces to her peers and abstruse wonders to me. Then it came again: a "good experiment." Part of a good experiment, she announced, is getting stuck. Then you have to get away. Go for a hike. An image of the campus in Boulder, Colorado, passed the screen.

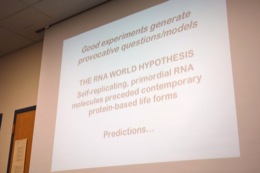

She had gone hiking there, once, when stuck. Eat ice-cream. It's not time wasted. You will be mulling over the problem, whether you know it or not. "Then it hits you." The moment came, if I recall correctly for this particular story, in the ice-cream shop. And then there it was again: another slide with "good experiment." "Good experiments generate provocative questions/models" Now I could see it. Both scientists and philosophers of science use the term "good experiment." But, as so often happens, the terms has slightly different meanings in each community. For the scientists, the notion of "good experiment" inclines towards the prospective. An experiment can be judged good now, in advance of its execution, if it shows promise that makes it now worth the investment of time and resources. Paula's criteria nearly all had that character. For philosophers of science, the notion inclines towards the retrospective. It is a success term. Allan judged Mendel's experiments excellent since, when we now look back at them, we find them to provide evidentially well-grounded new knowledge of great importance.

Does it make sense that the usage differs this way? I think it does. The experimental scientists' business is prospective. They want to know what to do now to gain knowledge later. The philosophers of science's business inclines toward the retrospective. We are occupied mostly in trying to understand just what the scientists have found and how they found it.

This is the start. Other speakers will be addressing the notion of good experiment. It is in their titles. Paolo Palmieri will speak on "What Makes a Good Experimentalist? Among Other Things, Good Senses . . ." Peter Distelzweig's title is "William Harvey’s Really Good (Aristotelian, Socratic, Whewellian) Experiments." Still others build their talks around the notion. Hey's "Uncertainty, Underdetermination, and the Units of Clinical Translation" was built around the question "What makes a good clinical biomarker experiment?" Margie Morrison answered the question with one word, simulation. There is much more to say on the question, but it won't be said here. John D. Norton

|