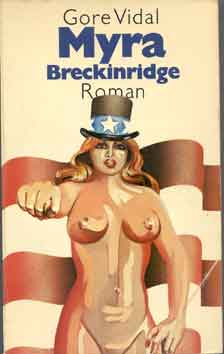

[NOTE: This essay was written in 2001 for inclusion in a Czech translation of Myra Breckinridge and Myron. The book's translator has so far yet to find a publisher. The illustrations below show the covers of five translations of the novels. From top: Netherlands, Mexico, Brazil, Netherlands, Portugal.]

IN 1968 - as her creator, Gore Vidal, so delicately put it nearly 20 years later - Myra Breckinridge "emerged like Athena from the head of Zeus (for non-classical scholars, Zeus Pappadapolis was once given, memorably, head by Athena Robsjohn-Gibbings, the furniture designer)." By Vidalís estimate, Myra's arrival measured 6 on the cultural Richter scale - a literary earthquake of major proportion in a dis-United States fighting an unpopular war and itself.

In America, and around the world, it was a year of liberation dreams and dashed hopes. For Americaís youth, the Sexual Revolution was gearing up for all-out war in the bedrooms and on the streets, and the anti-war movement had Eugene McCarthy as its shining presidential candidate to replace the warmongering Lyndon Johnson. In Europe as well, youth movements were aplenty. And who could forget the promising Prague Spring, followed - an impatient quarter century later - by the Velvet Revolution.

Upon its release in the spring of 1968, Vidalís ribald novel immediately became a No. 1 bestseller in the United States even before most critics had a chance to review it (largely because Vidal insisted that his publisher, Little Brown, not send advance review copies to the nationís book critics). Thus many of the people who bought the book might not have known what they were getting into. Vidalís 1964 novel, Julian, was a vivid tale of the apostate emperor who ruled Rome from 361-364 A.D. Three years later came Washington, D.C., his compelling insiderís look at American politics from 1937-1952, the very era in which Vidal came of age as the grandson of a U.S. senator and the son of a Roosevelt administration adviser.

In the long shadow of these two phenomenal literary successes - each well-reviewed, best-selling, and suitable for sophisticated and respectable readers - along came Myra B. and her punishing giant dildo.

Vidal wrote Myra Breckinridge in one month after a foray into a body of French literary criticism on what was called at the time "the New Novel." In a long, trenchant, blistering essays, "French Letters: Theories of the New Novel," published in the December 1967 edition of the literary journal Encounter, Vidal began: "To say that no one now much likes novels is to exaggerate very little. The large public which used to find pleasure in prose prefers movies, television, journalism and books of Ďfactí . . . Apparently novels sell not according to who wrote them but according to how they are presented." [N.B. circa 2001: Vidal seemed to recognize this trend long before American critics and scholars did.]

As well, he chides the study of novels by university intellectuals. "An even odder situation exists in the academy," he writes. "At a time when the works of living writers are used promiscuously as classroom texts, students themselves do little voluntary reading . . . The undergraduatesí dislike of reading novels is partly due to the laborious way in which novels are taught: the slow killing of the work through a close textual analysis."

In his pivotal essay, Vidal goes on to explore the work of French novelists-cum-literary-theorists Alain Robbe-Grillet and Nathalie Sarraute. Robbe-Grillet believed that it was impossible and undesirable to attempt to control a disorderly world by assigning it meaning in the form of plot and character. Sarraute agreed that novels cannot aptly or usefully portray human psychology, stating (as Vidal explains) that "only the absolutely presence of things can be recorded; certainly the depiction of human character is no longer possible." From this theorizing comes the New Novel, or Nouveaux Romancier, which sought to record the visual and aural details of life with absolute and precise accuracy - an act that turned a "novel" into a "text" and rendered it rather void of introspection and sensation.

And so from these ideas and this context arose Myra Breckinridge, Vidalís answer to the crisis of the novel. For the reader with the short attention span, Vidal wrote Myra Breckinridge in chapters that last anywhere from half a page to only four or five pages (with the notable exception of Chapter 29, the bookís penetrating climax). For an audience seeking only to read "books of fact," his uncompromising heroine tells us right at the start: "The novel being dead, there is no sense in writing made-up stories." Thus Myra proclaims herself to be The Absolute Teller of the Truth - a role that Vidal himself has played in his lifetime, especially when he writes about the hidden lies of American political history.

And for the reader who needs to be titillated by all things sexual, the pansexual Myra B. obliges with - but no, that would be telling.

IT WOULD BE NO EXAGGERATION to state that by the summer of 1968, Gore Vidal had become Americaís most talked-about author. Sales of Myra Breckinridge took off like a house afire, and in July 1968, during the Democratic National Convention in Chicago - an event marked by protests in the streets and violent police action against the protesters - Vidal appeared as a commentator on live television. His conservative opponent in debate was his long-time arch rival, William F. Buckley Jr. Before their face-to-face encounter ended, harsh words were exchanged - followed by years of lawsuits as each man sued the other for one reason or another.

That is the cultural whirlwind that surrounded Myra Breckinridge. But what of the book itself? Who is Myra Breckinridge? What is she? What does she represent? And could a book written in one month - as a response to a group of literary theorists trying to castrate the art form that Vidal so loved - really hold any lasting literary merit?

At the very least, Myra Breckinridge is a rollicking good read - funny, provocative, brilliantly written in prose that race along like a TGV. The novel shows Vidal at the peak of his power as a prose stylist. His command of language, rhythm and pace is often breathtaking in Myra Breckinridge, and his sense of humor is appropriately perverse. But Myra Breckinridge does have an inner life, one that emerged almost naturally from Vidalís incredibly well-read mind, which for more than half a century now has expounded on several recurring motifs.

Like Vidal - who has long maintained that all people are bisexual, although some choose to practice only same-sex or other-sex love - Myra believes in the fluidity of human sexuality, and she acts on her beliefs. Like Vidal - who spent his boyhood in movie theaters, and who, in 1992, wrote a little book called Screening History, about his emotional attachment to the silver screen - Myra has a passion for all things Hollywood. And in the character of Rusty Godowsky, whom Myra teaches the ultimate lesson in imperialism, Vidal creates an all-American boy to represent every Good American - all of whom he believes are being screwed by the corruption and lies of their government, a theme that runs through many of his essays and his seven interlocking novels of American history.

In "Myra & Gore," an edgy little 1974 book about Myra Breckinridge and its sequel, Myron, author John Mitzel points out that "Myra Breckinridge is a book about power. . .The excesses of Patriarchy have reduced women from their original status of Replenishers to mere decorative accessories and slave labor when not used for breeding." So Myra sets out to rebalance human society and skew it more toward The New Woman, "whose astonishing history," says Myra herself, "is a poignant amalgam of vulgar dreams and knife-sharp realities." As Mitzel puts its: "The old order was one of sexual repression and massive, unchecked procreation. The new order will be one of sexual expression. . .and reproductive sterility. "

Mitzel also sees Myra Breckinridge as a book that, once and for all, separates Vidal from the school of post-war American writers with which he had been associated for the first two decades of his literary career. The bookís wildly graphic sexual content assured this dissociation, as did its strong homosexual undercurrents. In fact, Mitzel discusses Myra as an important gay-themed novel because of the way it casts off the rigidity of societyís strict sexual boundaries in favor of a much more fluid and open exploration of human sexuality.

"By writing Myra," Mitzel says, "[Vidal] frees himself from inclusion in the Ď40ís bunch. Itís a prodigious effort to wrest oneself out of the time of oneís youth . . . Have any other male writers of that era done that? Escaped the insidiousness of that decadeís ultimate public values? . . . The coffin containing the corpse of Ď40ís culture is finally being laid to rest, killed off by one of its finest products."

Suffice it to say that Myra Breckinridge is not a realistic novel, like Washington, D.C. Nor should anyone take Myra or its sequel, Myron, to be an accurate reflection of Hollywood history, although Vidal - who began working in the movie and TV industries in the 1950s - certainly gets the banality and superficiality of Hollywood just right. Rather, Myra and Myron together form a ribald, two-volume parody of some of the most sacred elements of post-war American society, from an ever-expanding reverence for the moving picture and broadcast image, to the naÔve Middle American belief that all is well in Freedomís Land (as Vidal ironically refers to his country) when, in fact, the American corporate government continues to whittle away at its citizensí personal rights.

FOR VIDAL, the accidental genius of Myra Breckinridge turned a page in his literary career. It was the authorís first novel of a variety that he now calls his "inventions"- books in which he manipulates realities and invents parodic worlds as a way of satirizing American culture. Vidal has now written five such inventions: Myra Breckinridge (1968); Myron (1974); Duluth (1983); Live from Golgotha (1992); and The Smithsonian Institution (1998). Two other novels - Messiah (1954) and Kalki (1978) - tell futuristic stories of religious death cults, although they are more often classified in Vidalís canon as science-fiction than as "inventions."

It would seem that Vidal did not intend to become an author known for books in this genre. After all, he began writing Myra Breckinridge almost by accident, he finished the book in one month, and he claims that Myraís startling climactic revelation about her sexual past came to him "from out of the blue" while in the midst of writing the book. In a particular sense, the book almost seemed to write itself - or, perhaps, the "real" Myra Breckinridge channeled her thoughts through Vidalís pen and used him as an agent to tell her "true" story.

A few years later, while working on fragments of another novel, Vidal ended up writing Myron, a sequel to Myra Breckinridge. Whereas the first book took place in a time period contemporary with the bookís publication, Myron thrust the character back in time to 1948, an era in which American culture was even more prim and proper than the evolving 1960s.

But the befuddled and straight-laced Myron Breckinridge doesn't spend his time in the past entirely (or even wholly) as himself: After a while, he finds himself inhabiting the body of Maria Montez (1920-1951), a B-movie actress of the era. And to make matters even worse, it isnít just Myron who goes back in time: Myra goes back with him, and from chapter to chapter, the reader never knows which personality will come to the surface and take over the narrative.

If Myra Breckinridge arrived in bookstores in 1968 at a time of cultural and political upheaval in America, Myron came about in 1974 at a time when this upheaval had been muted by a conservative-led malaise. Richard Nixon was president - although soon he would resign in disgrace - and the U.S. Supreme Court had refused to protect the absolute right to publish "obscene" material. Rather, the Court ruled that "community standards" should determine what is obscene. So a book that is perfectly acceptable in one town might be banned in another town.

To combat the Supreme Courtís "mad way with the First Amendment," Vidal decided to remove the "dirty" words from his book and replace them with "cleaner" ones - the names of the Supreme Court justices who participated in the ruling. Thus "to fuck" becomes "to burger," after Chief Justice Warren Burger. A "pussy" becomes a "whizzer white," after Associate Justice Byron White (nicknamed "Whizzer" in college because he was a speedy football star). And a "dick" becomes a "rehnquist," after William H. Rehnquist, an associate justice in 1974 who became the Courtís chief justice in 1986 when Burger retired from the court.

Myron remained in this form for a decade in paperback editions. But in 1985, when Vidal published the two books together as Myra Breckinridge and Myron in a new hardcover edition, he decided that "Myron should conform to Myra." Thus he removed the "burgers," "rehnquists" and "whizzer whites" and restored their more graphic anatomical meanings.

UPON ITS PUBLICATION in 1974, Myron didnít make as big a splash as its predecessor did six years earlier. In the intervening years, Vidal had published Burr , his well-received, best-selling historical novel of former Vice President Aaron Burr, a man whose scandalous, misunderstood life appealed to Vidal with his ideas about Americaís distorted sense of its own history. Thus audiences had come to expect a certain kind of novel from Vidal, and Myron didnít fit that mold. Also, the years between Myra Breckinridge and Myron welcomed a surge in the publication of graphic writing, and Vidalís novel surely was not pornography (or at least not pornographic enough to please true porno-philes!). If you throw in the rise of more explicit cinema, then by 1974 the shock value of a novel like Myron had worn off, and its satire had come to seem more strident and obvious.

And finally, in 1970, there was the film version of Myra Breckinridge, considered by some critics to be the worst movie ever made. The poster for the movie proclaimed: "At last, the book that couldnít be written is now the motion picture that couldnít be made!" But it should have said "the motion picture that shouldnít be made." Perhaps another director with a better cast could have made a provocative movie of Myraís shocking tale. But the young British director Michael Sarne, saddled with Raquel Welch in the title role and a withered Mae West as Letitia Van Allen, simply became overwhelmed by too many competing factors, and his movie was a disaster. Vidal disowned the production, and for decades it was not even available on videotape or DVD.

Vidal notes that after the release of the awful Myra movie, paperback sale of his novel stopped. So its sequel four years later was hardly likely to be greeted with a wave of commercial enthusiasm. In the time that has passed since the mid-1970s, Myra Breckinridge has regained some of her stature as a landmark novel of its kind and as one of Vidalís most raucous tales. She and her sequel remain in print today in paperback, and Vidal himself continues to be as controversial as ever, of late largely for his essays on the American empire. Still, nothing in the authorís vast canon holds the unique place that Myra Breckinridge does: Ahead of its time in 1968, the 21st Century still hasnít caught up with her, and one suspects it probably never will.

©Copyright 2005 by

Harry Kloman

University of Pittsburgh

kloman@pitt.edu