Gore Vidal's Essays, Interviews and Memoirs:

1963-Present

Just as Vidalís work as a

playwright and screenwriter came

about in part through financial necessity, so did his work as an essayist.

In the early 1950s, he found that he could make some extra income writing

for magazines and journals, and so he did. Soon he came to enjoy this

role, although he could not have known these little pieces - which grew

bigger as time went on - would bring him perhaps his widest fame. Many

Vidal enthusiasts now consider his essays to be more important

than his

novels, and even those who like his novels realize that they expound upon

the themes he examines so well in his critical nonfiction. A number of

European publishers have enjoyed and published Vidalís essays, although

surprisingly, not as widely as his novels. His essays have been

periodically translated into French, German, Spanish, Italian, Portuguese,

Serbian and Hungarian. Heís also a popular commentator in the United

Kingdom, where all of his American essay collections have appeared, along

with a few unique British collections.

Just as Vidalís work as a

playwright and screenwriter came

about in part through financial necessity, so did his work as an essayist.

In the early 1950s, he found that he could make some extra income writing

for magazines and journals, and so he did. Soon he came to enjoy this

role, although he could not have known these little pieces - which grew

bigger as time went on - would bring him perhaps his widest fame. Many

Vidal enthusiasts now consider his essays to be more important

than his

novels, and even those who like his novels realize that they expound upon

the themes he examines so well in his critical nonfiction. A number of

European publishers have enjoyed and published Vidalís essays, although

surprisingly, not as widely as his novels. His essays have been

periodically translated into French, German, Spanish, Italian, Portuguese,

Serbian and Hungarian. Heís also a popular commentator in the United

Kingdom, where all of his American essay collections have appeared, along

with a few unique British collections.

In addition to all of the nonfiction written by Vidal, numerous

scholars have written book-length works about him. The largest of

these is Fred Kaplanís 1999 authorized biography, although Vidal - who

gave Kaplan access to his diaries and letters - ultimately disavowed

Kaplanís effort, apparently concerned that the book would not represent

him as he had hoped to be represented. The first scholarly tome about

Vidal, an eponymous critical study of his work, appeared in 1968 and was

written by Ray Lewis White. Six years later came two books: Bernard F.

Dickís The Apostate Angel: A Critical Study of Gore Vidal; and

Myra & Gore: A Book for Vidalophiles, by John Mitzel with Steven

Abbott, consisting of a socio-sexual reading of Myra Breckinridge

and a lengthy interview with Vidal reprinted from the journal Fag

Rag. Robert F. Kiernan published another eponymous critical study in

1983; Jay Parini, Vidalís literary executor, compiled Gore Vidal:

Writer Against the Grain, a collection of scholarly essays, in 1992;

and Susan Baker and Curtis S. Gibson published Gore Vidal: A Critical

Companion in 1997, offering a series of original essays on Vidalís

books from various critical perspectives (deconstructive, feminist,

Marxist, new historicist, etc.). Finally, for those fluent in French,

thereís Nicole Bensoussanís Gore Vidal: líiconoclaste, a 1997

critical study, not yet translated into English, that covers everything

from Myra and the other inventions to the novels of ancient

and American history.

written by Ray Lewis White. Six years later came two books: Bernard F.

Dickís The Apostate Angel: A Critical Study of Gore Vidal; and

Myra & Gore: A Book for Vidalophiles, by John Mitzel with Steven

Abbott, consisting of a socio-sexual reading of Myra Breckinridge

and a lengthy interview with Vidal reprinted from the journal Fag

Rag. Robert F. Kiernan published another eponymous critical study in

1983; Jay Parini, Vidalís literary executor, compiled Gore Vidal:

Writer Against the Grain, a collection of scholarly essays, in 1992;

and Susan Baker and Curtis S. Gibson published Gore Vidal: A Critical

Companion in 1997, offering a series of original essays on Vidalís

books from various critical perspectives (deconstructive, feminist,

Marxist, new historicist, etc.). Finally, for those fluent in French,

thereís Nicole Bensoussanís Gore Vidal: líiconoclaste, a 1997

critical study, not yet translated into English, that covers everything

from Myra and the other inventions to the novels of ancient

and American history.

In general, Vidalís essays discuss four topics: literature, politics, sex

and himself. Rarely is a topic exclusive to one essay, for Vidal finds

plenty of crossovers between them. He has used this work to develop a

political ideology that he continued to explore in his novels of American

history, and many of his other novels, particularly his inventions,

clearly dramatize his assertions about human sexuality. As for his views

on literature: They have led him to write particular kinds of novels,

although literary subjects rarely come up in the novels themselves. Vidal

has long maintained that the novelist, once a respected category of artist

in American society, has lost his prestige to the moving picture - a

medium in which Vidal himself has joyfully dabbled for decades.

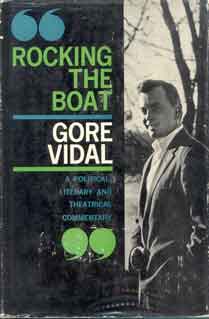

Rocking the Boat (1962) After 10 years of

publishing essays periodically in both popular and literary magazines,

Vidal finally collected them in this volume, which includes pieces written

between 1951 and 1961. The oldest piece in the book is "The Making of a

Hero and a Legend: Richard Hillary," a book review that first appeared in

The New York Times Book Review on Feb. 11, 1951. (Interestingly, in that

period, the daily New York Times refused to review Vidal's novels because

he wrote the homosexual novel The City and the Pillar in 1948.)

Vidal divides Rocking the Boat - the title is somewhat

self-congratulatory - into four parts: Politics, Theater, Books, Personal.

He opens it with an introduction in which he tells us, with characteristic

modesty: "Rereading oneís own past commentary is like going through an

album of old photographs. Did I really part my hair in that peculiar way?

Was I ever that thin? I have kept several unflattering snapshots in the

interest of truth, and I have done almost no touching-up." Still, unable

to resist amending himself, he includes an appendix that adds a few

thought to a few of the essays.

One of the more significant essays in Rocking the Boat is "A

Note on the Novel," originally published in 1956 in the New York Times

Book Review. In the essay, Vidal begins to expound upon a theme that he

would return to often: Despite the presence of good novelists, the novel

is dead or dying, he argues, because readers no longer give the form the

kind of cultural weight they once did. Finally, Rocking the Boat

contains the essay "Ladders to Heaven: Novelists and Critics of the

1940s," which Vidal first published in New World Writing #3, a

multi-authored 1953 paperback anthology of essays and short stories.

Whatís significant here is that Vidal originally published the essay under

the pseudonym "Libra" because he also had a short story ("The Ladies in

the Library") under his own name in the book, and because he was one of

the founders of the anthology series and didnít want to appear to be too

prolific in its pages. So the essayís re-publication here unmasks yet

another Vidalian

pseudonym.

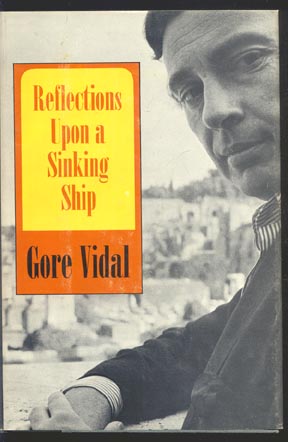

Reflections Upon a Sinking Ship (1969)

Having rocked the boat seven years ago with his first well-received essay

collection, Vidal felt the time had come to declare the ship duly sunk and

to reflect upon its demise. "With no melodramatic intent," he writes in

the bookís preface, "I have selected a title which seems to me altogether

apt this bright savage spring with Martin Luther King dead and now Robert

Kennedy. The fact that these deaths occurred at a time when the American

empire was sustaining a richly deserved defeat in Asia simply makes for

added poignancy, if not tragedy." And so this collection takes on a

heavier tone right from the start. What follows are some of his most

provocative essays of the 1960s, including his touchstone piece "The Holy

Family," a look at the Kennedys and their Camelot that first appeared in

Esquire, and "The Manchester Book," another Kennedy-related piece. We also

get "French Letters: Theories of the New Novel," an incisive look at

trends

in fiction writing that would form the genesis for his novel Myra

Breckinridge. The long, detailed, highly intelligent essay first

appeared in the journal Encounter in December 1967.

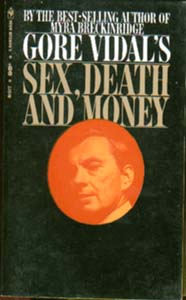

Sex, Death and Money (1969)

The huge success of Myra Breckinridge in 1968 led Vidalís

paperback publisher, Bantam, to throw together a collection of his essays

in pocket book form for consumption by mass audiences. The book contains

only one essay - "The Television Blacklist," about the homespun Ď50s radio

and TV personality John Henry Faulk - that appears nowhere else in Vidalís

collected essays. "Sex, death and money are the essential interests of the

naked ape," he writes in a five-page introduction. The essays in the book

then go on to cover the gamut of his usual themes.

Homage to Daniel Shays (1973)

So popular had Vidalís essays become with readers that - a mere four years

after his previous collection, and barely a decade after his first one -

Vidalís new publisher, Random House, brought together the content of both

earlier books, freshened it up with his writing since 1968, and published

it all together in one volume covering his writing from 1952 to 1972.

Arranged chronologically, the pieces include the hilarious "Doc Reuben" (a

rout of Everything Youíve Always Wanted To Know About Sex), tart

pieces on his old friends AnaÔs Nin and Norman Mailer, and poignant

tributes to Eleanor Roosevelt and Yukio Mishima. The 44 pieces in the book

show Vidalís full bloom as a challenging and important American essayist.

Vidal had originally planned to publish the book under the title On

Our Own Now, a line taken from his essay on Mrs. Roosevelt. But

shortly before publication - and after Random House had distributed review

copies with the first title - Vidal added the titular essay, a grim

examination of money, power and property in America, and changed the

bookís title accordingly. In England, however, where the patriot Daniel

Shays - who led an anti-tax, anti-tyranny rebellion just after the

American revolution - was less well known, the book appeared in hardback

as Collected Essays: 1952-1972 and in paperback as On Our Own

Now.

Matters of Fact and of Fiction (1977)

No sex here: just politics and literature, discussed in 17 essays on Louis

Auchincloss, Italo Calvino, Vladimir Nabokov, Tennessee Williams, E.

Howard Hunt, Ulysses S. Grant, the Adamses, Robert Moses and other people

and topics. The collection begins with a witty piece on the banality of

best-selling fiction, ends with his "State of the Union" address first

printed in Esquire, and in between features "The Hacks of

Academe," an important piece in which Vidal lays out his criticism of

literary scholarship. Itís a leaner, headier collection of essays than its

immediate predecessor, and the photo of Vidal on the back of the dust

jacket finds him stroking his chin ponderously with his index finger.

Sex Is Politics and Vice Versa (1979)

For the January 1979 issue of Playboy, Vidal wrote a provocative

essay - beautifully illustrated by the magazine - on the relationship

between his two favorite topics. Later that year, Los Angeles book

publishers Stathis Orphanos and Ralph Sylvester issued the essay in a fine

press limited edition, most copies bound in white cloth, but with a

limited number bound in black leather. The slender, unpretentious volume

is unique in Vidalís canon. On a colophon page at the end of the book, we

learn that Orphanos and Sylvester published "a limited edition of 330

copies. 300 are numbered, 26 lettered, and four bear the printed name of a

recipient." The four people who received personal copies were Orphanos,

Sylvester, Vidal - and Christopher Isherwood, Vidalís long-time friend,

who was also well

versed in the exigencies of sex and politics. The essay itself takes on

some of the 1970sí most odious anti-sex, anti-freedom Rightists, like

Phyllis Schlafly, Orrin Hatch, Richard Viguerie and Norman Podhoretz.

Views from a Window: Conversations with Gore Vidal

(1980)

Teacher/writer Robert

Stanton, who published a book-length bibliography of Vidal in 1978, has

compiled Vidalís many published interviews into this one volume. But

rather than merely reprinting the interviews, he arranges the comments by

topic and tells us where Vidal made each set of remarks. So in a section

on "Sexuality," for example, we first read several pages of material from

an interview in Oui magazine, followed without interruption by

material from an

interview first printed in The Listener, and then by material

from a chat Vidal had with Stanton (one of several conducted exclusively

for this book). It all flows together smoothly in Q&A form, thanks to

Stantonís helpful organization and Vidalís gift for trenchant gab. Stanton

draws his material from 27 interviews Vidal gave to nearly two dozen

publications from 1960 to 1979. The clarity and consistency of his voice

dominates this well-done book, originally published by Lyle Stuart and

easy to find for sale on used book sites.

The Second American Revolution (1982)

Although the title of this 19-essay collection would seem to indicate

(correctly) that it deals more with politics than anything else, the book

still has some of Vidalís best 1970s writing about sex and literature. For

those who donít own the fine press special issue of Sex Is

Politics, Vidal reprints the essay here for the first time. The title

essay is a powerful indictment of homophobia in America - so powerful, in

fact, that Vidalís U.K. publisher scrapped the American title of the book

and published the collection as Pink Triangle and Yellow Star.

Another highlight is "Christopher Isherwoodís Kind," a quietly moving

tribute to his friend.

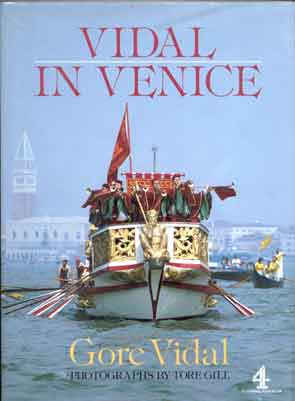

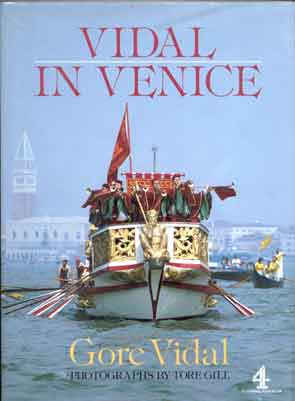

Vidal in Venice (1985)

This exquisitely mounted cocktail table book, printed on glossy paper, is

rife with photo of glorious Venice taken by Tore Gill. Vidal begins the

narrative by talking about his familyís roots in Europe, and Gillís

photographs reveal sites possibly linked to his family name, like a

"Vidale" family gravestone in Friuli, or the "Rio de S. Vidal," a small

canal that passes behind the Church of S. Vidal. The rest of the book

explores the history, culture and splendor of a city that Vidal calls

"perhaps the most beautiful clichť on earth." Although no other authorís

name appears on the bookís front cover, the title page discreetly says,

"Edited by George Armstong." In fact, according to Vidalís biographer Fred

Kaplan, Armstrong wrote virtually all of the text for the book, and

despite Vidalís insistence that Armstrong get credit for it, the publisher

demanded that Vidalís name appear as the sole author. To accompany the

printed edition of this book, Vidal did a video edition of the

text for British television. It's available commercially on two 55-minute

videos. Pictured here, above left, is the vibrant front cover of the U.K.

edition of the book. A different, less vibrant image appears on the cover

of the

U.S. edition (above right). But the

back cover of both editions pictures Vidal

sitting casually on the Doge's throne in Venice.

Armageddon? (1987)

This book testifies to Vidalís popularity in the United Kingdom: Although

many of its 20 essays, written from 1983 to 1987, would appear the next

year in the American collection At Home, U.K. audiences

apparently couldnít wait. So Vidalís U.K. publisher issued this

collection, one of three with no page-for-page American counterpart (in

the way that The Second American Revolution and Pink

Triangle and Yellow Star are identical books with different titles).

In his brief preface, Vidal admits that the book has no theme: "Over the

years," he writes, "I have noted with what nervousness writers apologize

for collections of random pieces that they have written. They seem to

think that a collection of essays ought to have a single numinous theme,

like dentistry or the writerís own sweet self." Still, the essays here

tend to discuss literature and politics, with an occasional personal note

thrown in. The title piece - notice the question mark - explores "the

ancient Acting President" (i.e. Ronald Reagan) at the end of his

administration, although the essay wanders through a variety of

contemporary topics, ending with talk of Mikhail Gorbachev, Norman Mailer,

and Vidalís proposed constitutional amendment that no president be allowed

to believe in an afterlife.

At Home (1988)

This American essay collection, not published per se in the U.K.

because of Armageddon?, covers the years 1982 to 1988, thus

starting one year earlier than its British cousin and ending one year

later. It contains 24 essays, several of them rather personal and

autobiographical: "At Home in Washington, D.C.," "At Home on a Roman

Street," "Mongolia!" and "How I Do What I Do If Not Why" among them. He

also writes about Richard Nixon, Tennessee Williams, Anthony Burgess and

"Ronnie and Nancy: A Life in Pictures." This book contains the same

introduction as Armageddon?, confessing to a lack of unifying

theme, although on the whole, the writing in At Home suits its

title.

A View from the Diners Club (1991)

Hereís a unique-to-the-U.K. edition with no American counterpart

whatsoever: Americans would have to wait for the comprehensive United

States after the publication of At Home, but Vidalís British

readers got this collection of 16 essays written from 1987 to 1991. He

divides them into two categories, "Book Chat" and "Politics," and

discusses Henry Miller, Dawn Powell, Oscar Wilde, H.L. Mencken, Ted

Kennedy and "The National Security State." In the preface he says, "Since

I shall not write a memoir, I have included more personal references - or

rather my personal responses to others - than one ought, strictly, to do

in reviewing." Of course, he would write a memoir, thereby

invalidating his long-time assertions that he would never do any such

thing.

Screening History (1992)

"As I now move, graciously, I hope, toward the door marked Exit," Vidal

begins this unusual little book, "it occurs to me that the only thing I

ever really liked to do was go to the movies." Written for and delivered

at Harvardís William E. Massey Sr. Lecture Series in the History of

American Civilization, and published by Harvard University Press,

Screening History is a memoir about both the movies and Vidalís

love for them. The book is handsomely illustrated with glossy photos of

old movies and some images of Vidalís childhood, including a famous shot

of his 10-year-old former self behind the controls of a prototype Hammond

Y-1, an airplane he actually flew in 1936, thus making him the youngest

person at the time to fly a plane. Of course, politics creep into the

narrative, especially when he writes about Lincoln on film. The cover of

the book shows Vidal alone in an empty movie theater, looking over his

shoulder at the camera, while on-screen is a scene from Gore Vidalís

Billy the Kid, a teleplay he wrote in 1989 based on his 1955 drama

for live TV. The scene features Val Kilmer as Billy and Vidal in a cameo

as a preacher.

The Decline and Fall of the American Empire

(1992)

The American Presidency (1998)

Odonian Press, which takes its name from the Ursula Le Guin novel The

Dispossessed, publishes books of liberal-to-Left social and political

ideology, donating at least 10% of its annual after-tax income to

organizations working for social justice. So naturally Odonian finds

Vidalís views on corporate and political empire-building a natural fit. In

these two little books, each 88 pages long (plus index), Vidal discusses

American politics in his usual pungent way. The essays in The Decline

and Fall of the American Empire have all appeared elsewhere; the

essays in The American Presidency are adapted from a television

special Vidal did for The History Channel and the BBC. Nonetheless,

bringing the material together thematically has created two nice pocket

books of political thought, each presented attractively with colorful

glossy covers.

United States (1993)

This weighty tome is more than a cocktail-table book: At 1,295 pages in

length, it could serve as the entire cocktail table. Pulling together

virtually all of his essays published from 1952 to 1992, itís the

definitive collection for Vidalophiles or for people who happened onto his

writing late in his career and who want to catch up with his nonfiction

canon. The book includes the essays written after At Home, but

most of United States has appeared in one or more of the earlier

collections. Still, for putting it all in one place - and perhaps for

having attained "venerable" status" - Vidal won the

National Book Award for nonfiction, and despite this bookís size, it sold

well and went into numerous printings both in the U.S. and England.

Palimpsest: A Memoir (1995)

For at least a quarter of a century, Vidal always swore that he would

never write a memoir. But when biographers began to show interest in his

life, he decided that heíd better get his own version on the record before

it was to late. The result is one of the most entertaining and beautifully

written books in his canon, although not the revelatory work some had

hoped to read. Palimpsest is a reflection on a variety of

histories - political, literary, personal - and the intersections of the

three. Covering Vidal's life from before his birth, in 1925, and stopping

in 1962, as he approached 40 - with a brief flash forward to the

contemporary Vidal - itís often fond and gentle, yet sometimes almost

pathologically cruel and bitter. (Vidal continues the story of his life in

his 2006 sequel, Point to Point Navigation). To people unfamiliar

with his life and work, this memoir will read like a brash rumination on

the political figures and literati of the 20th-century American Empire. To

his followers, it fills in a few (but only a few) of the

intriguing emotional gaps of a man who says he fell in love once at age 14

and has never felt the need to do so again. Thus in the end he declares

this book to be a love story, for he writes most movingly about Jimmie

Trimble, the boy who made him feel whole like no one has since their

time together in the 1930s. Vidal says he loses concentration when he

makes eye contact with someone. Paul Newman, his friend since the 1950s,

once told him, "Iíve never understood how you loners do it." Itís a

compelling question, but Palimpsest ultimately provides no

answer.

Virgin Islands (1997)

Once again comes a collection that has no American counterpart: Published

in the U.K. only, it presents essays written from 1992-1997. Part I covers

literature, but Parts II and III are all about politics, as his essays in

recent

years have increasingly become. From FDR and Truman to the United Nations

and American imperialism, itís all here once more. He titled this book

Virgin Islands, he says, because it follows United

States and is thus a dependency of that larger book. At the end of

the book, just for his British fans, he presents a map of the United

Kingdom showing the location of U.S. military installations there and a

charting showing American military spending on those installations.

Sexually Speaking: Collected Sex Writings

(1999)

The small gay and lesbian Cleis Press - born in Pittsburgh, but now

located in San Francisco - brought together 14 of Vidalís essays on sexual

matters, from "Sex and the Law" and "Sex Is Politics" to "Eleanor

Roosevelt" and "Jíaccuse," his brief 1998 tract accusing Republican U.S.

Sen. Trent Lott of murder for inciting fatal violence against homosexuals.

The book includes an introduction by editor Donald Weise, a reprint of the

interview by Mitzel and Abbott from the 1974 book Myra & Gore,

and an interview with Vidal conducted by Larry Kramer in 1992. Vidal

granted the rights to his essays free of charge for this book, which is

the biggest ever published by Cleis in terms of press run and author

prestige. The book is available in both hardback and paperback and, as of

April 2001, in a Spanish translation, Sexualmente Hablando: Articulos

Escogidos Sobre Sexo.

The Last Empire (2001)

What fortuitous timing: Vidal's first essay collection of the 21st Century

arrived in stores right in the middle of the controversy over his

involvement in the

execution of Timothy McVeigh, the conviced bomber of the Murrah

Building in Oklahoma City. In May 2001, just weeks before McVeigh's first

execution date - and before they discovered that the FBI withheld

documents from McVeigh's defense team - Vidal announced he would be one of

McVeigh's five invited witnesses and that he would write about the

execution for Vanity Fair. The two began a correspondence when

McVeigh read Vidal's October 1998 Vanity Fair essay "The War at

Home," which appears in this collection as "Shredding the Bill of Rights."

In interviews about McVeigh, Vidal said he shared the confessed killer's

views about the loss of personal freedom in American and referred to

McVeigh as "a fine young man." And while he did condemn McVeigh's actions,

few newspaper readers saw the distinction between the action and the

philosophy that led to it.

The Last Empire contains 48 pieces on literature and politics,

most of which were first collected in the 1997 U.K. volume Virgin

Islands. Kenneth Starr, Frank Sinatra, John Updike, Richard Nixon,

Bill Clinton, Mark Twain: They all get the Vidalian treatment. Vidal

published this book in the wake of the bizarre presidential election

between Al Gore and George W. Bush, and to make his book as timely as

possible, he added this foreword to one of the essays: "I am writing this

note a dozen days before the Inauguration of the loser of the year 2000

presidential election. Lost republic as well as last empire. We are now

faced with a Japanese seventeenth-century-style arrangement: a powerless

Mikado ruled by a shogun vice president and his Pentagon warrior

counselors. Do they dream, as did the shoguns of yore, of the conquest of

China? We shall know more soon, I should think, than late. Sayonara. Gore

Vidal - 11 January 2001."

Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace:

How We Got To Be So

Hated (2002)

This little book, which takes its title from a term coined in 1947 by the

American historian Charles A. Beard, is one of Vidal's most controversial

in decades. It began as an essay for Vanity Fair on the Sept. 11 terrorist

attacks and, when Vanity Fair declined to publish the essay, Vidal

published it, along with a few other related essays, in an Italian book he

called La fine della libertŗ: Verso un nuovo totalitarismo?

(which means "the end of liberty: toward a new totalitarianism"). Soon,

though, he found an American publisher for the material in the Italian

book, which for U.S. release he retitled Perpetual War for Perpetual

Peace: How We Got To Be So Hated. Both the Italian and American

editions of the book contain the Sept. 11 essay along with several other

previously published essays that express Vidal's views about America's

vanishing liberties. In fact, this book and its followup, Dreaming

War, have been very popular

around the world.

In his five-page introduction to Perpetual War for Perpetual

Peace, Vidal discusses the history of his unpublished Vanity Fair

piece and quotes from a piece by Arno J. Mayer that The Nation declined to

publish. The Mayer essay speaks of the United States' history of

"preemptive state terror" in the Third World since World War II. Next

comes the essay "September 11, 2001 (A Tuesday)," the piece originally

written for Vanity Fair. Here Vidal discusses at length the implications

of what happened to the World Trade Center on the 21st Century's first day

of infamy. The essay ends with a 20-page chart detailing American military

operations around the world from 1949 to the present.

Vidal calls the second section of the book "How I Became

Interested in Timothy McVeigh and Vice Versa." This begins with a brief

introduction about his relationship with McVeigh and then presents two

essays: "The Shredding of the Bill of Rights," which appeared in the

November 1998 issue of Vanity Fair under the title "The War at Home"; and

"The Meaning of Timothy McVeigh," which appeared in the September 2001

issue of the magazine.

The book's third section, "Fallout," contains a very

brief introduction to a copy of Vidal's Aug. 27, 2001, letter to FBI

director-designate Robert S. Mueller III. The letter chides Mueller with

evidence that Timothy McVeigh did not act alone in bombing the Murrah

building in Oklahoma City. "Now that McVeigh has already been injected

into a better world," he writes in the letter, "I am sure that the

bureau's choice of explanation to my inquiry will be a difficult one." He

goes on to ask whether the FBI merely conducted an incompetent

investigation, or whether the bureau knowingly withheld evidence. He then

presents a 10-point Bill of Rights written by McVeigh on May 28, 2001.

The last two sections of the book present two more of Vidal's previously

published essays: "The New Theocrats," reprinted from a 1997 issue of The

Nation, in which he discusses a moralizing conservatism that breeds an

"old-fashioned American stupidity where a religion-besotted majority is

cynically egged on by a ruling establishment"; and "A Letter To Be

Delivered" - reprinted from Vanity Fair, and written on Nov. 7, 2000 - in

which he writes an open letter to the soon-to-be-elected president. To

this final piece he adds a preface and a footnote - written "a dozen days

before the inauguration of the loser of the 2000 presidential election" -

that sees the Bush-Cheney presidency as one of "a powerless Mikado ruled

by a shogun vice president and his Pentagon counselors."

Much of the material in Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace appears

in The Last Empire, Vidal's 2001 essay collection. So there's

really very little new Vidalian content in Perpetual War for Perpetual

Peace or its Italian counterpart tthat you couldn't already get at a

library, although the publication of the essay about Sept. 11, and the

material relating to it, is clearly very significant.

Dreaming War:

Blood for Oil and the Cheney-Bush Junta (2003)

In October 2002, Vidal wrote another essay about Sept. 11 in which he

speculated on whether the Bush administration knew about the attack in

advance and let it happen anyway. This essay anchors Dreaming War:

Blood for Oil and the Cheney-Bush Junta, a sort of companion book to

Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace. The essay first appeared in

the Oct. 27, 2002, issue of the U.K. newspaper The Observer under the

title "The Enemy Within," and it was illustrated on the British

newspaper's

front page. Shortly before its U.K. publication, it

appeared in the 2002 Italian book Le menzogne dell'impero e altre

tristi veritŗ, another small collection of Vidal's writings, opening

with the Observer essay. That book - its title means "the mendacities of

empire and

other sad truths" - explores "why the Bush-Cheney petroleum junta wants

war with Iraq." It contains 10 political essays selected from The Last

Empire along with the essay from The Observer.

For Dreaming War, Vidal retitles the Observer essay "Goat

Song: Unanswered Questions - Before, During, and After 9/11" and follows

it with another original piece: a short essay-cum-diatribe on Louis Menand

and his October 2002 piece in The New Yorker in which Menand dissected and

criticized Vidal's and Noam Chomsky's books on the Sept. 11 attacks.

Naturally, Vidal sets Menand straight and charges that Menand

misrepresented and misunderstood his position. The rest of Dreaming

War reprints seven political essays from The Last Empire and

three essays published in journals since The Last Empire appeared

in 2001. It closes with a 15-page interview with Vidal conducted by Marc

Cooper.

In a brief "Note" at the start of Dreaming War,

Vidal declares himself to be trading in a literary form that's new to him:

the pamphlet, which he calls "the oldest form of American political

discourse." Thus he dedicates the book to Publius - the pseudonym under

which Alexander Hamilton, James Madison and John Jay published the

numerous Federalist papers - and even includes Perpetual War for

Peace in the genre.

Inventing a Nation: Washington, Adams, Jefferson

(2003)

In Vidal's little history book - and this time, it's the real thing,

not a novel - the founders of the United States of America become

crystal clear about the need for a federal constitution after the Shays

rebellion of 1786-87. Before it, a Federalist faction favored a strong

central government, while an anti-Federalists (later "Republican") faction

favored wider states' rights. But when Shays rose up against the moneyed

class and fought for the overtaxed poor, "there were no Federalists, no

future Republicans," Vidal writes, "only frightened men of property."

Still, Vidal admires many things about many of these men. Washington:

honest, altruistic, majestic, a mediocre general who led by force of

character. Adams: misanthropic, anti-aristocratic, well-meaning, and a bad

judge of human nature. Jefferson: a dreamy existentialist who wanted a

convention once a generation to re-examine and revise the federal

constitution. And of course, the immutably wise old Franklin, whom Vidal

sees as having been rendered by history from an "eerily prescient voice"

into "the jolly fat ventriloquist of common lore, with his simple maxims

for simple folk." He especially praises Franklin for predicting that "the

People shall become so corrupted as to need Despotic Government, being

incapable of any others."

Still, Vidal admires many things about many of these men. Washington:

honest, altruistic, majestic, a mediocre general who led by force of

character. Adams: misanthropic, anti-aristocratic, well-meaning, and a bad

judge of human nature. Jefferson: a dreamy existentialist who wanted a

convention once a generation to re-examine and revise the federal

constitution. And of course, the immutably wise old Franklin, whom Vidal

sees as having been rendered by history from an "eerily prescient voice"

into "the jolly fat ventriloquist of common lore, with his simple maxims

for simple folk." He especially praises Franklin for predicting that "the

People shall become so corrupted as to need Despotic Government, being

incapable of any others."

Vidal's narrative in Inventing a

Nation seems to meander at time but all in all flows quite

smoothly, moving backward and forward within his 18th Century time frame

whenever he needs to make connections. Sometimes he even moves

very forward, drawing parallels between his central historical

events and the emerging history of the 21st Century. The Sept. 11

terrorist attacks pop up, as does Britain's New Labor prime minister, Tony

Blair, whose victory Vidal sees as a reminder of the pre-destiny - or at

least, the consistency - of national character, for better or for worse.

Money and power are the villains of the piece, although Vidal never goes

so far as to suggest that the People would do any better.

Imperial America:

Reflections on the United States of

Amnesia (2004)

As he did with his two little essay collections, Perpetual War for

Perpetual Peace and Dreaming War, Vidal calls this small

book of essays a pamphlet. A mere 181 pages long (including index), it has

about 40 pages of new writing and one essay that has not previously

appeared in book form. The oldest essay dates back to 1981, and the newest

he wrote for this book. All of the essays examine Vidal's views on the

American empire, and having these particular pieces together in one volume

shows the progression of his central argument during the last quarter

century.

Imperial America begins with "State of the Union: 2004," a

followup to his other "State of the Union" essays throughout the years.

But in the essay, Vidal says virtually nothing about the state of America

today: Mostly, it's a reminiscence about past state of the union

addresses, which he gave on speaking tours and on David Susskind's PBS

talk show. After that comes a longer, more substantial piece of new

writing, "The Privatization of the American Election," in which Vidal

examines the record so far of the Bush administration, including massive

cuts in veterans' benefits at the same time Bush portrays himself as being

pro-military. Referring to the "ever-reckless Bush-Cheney junta," Vidal

says, "Not since the 1846 attack on Mexico in order to seize California

has an American government been so predatory. . .He is like a man in one

of those dreams who knows he is safe in bed and so can commit any crime he

likes in his voluptuous alternative world."

Imperial America begins with "State of the Union: 2004," a

followup to his other "State of the Union" essays throughout the years.

But in the essay, Vidal says virtually nothing about the state of America

today: Mostly, it's a reminiscence about past state of the union

addresses, which he gave on speaking tours and on David Susskind's PBS

talk show. After that comes a longer, more substantial piece of new

writing, "The Privatization of the American Election," in which Vidal

examines the record so far of the Bush administration, including massive

cuts in veterans' benefits at the same time Bush portrays himself as being

pro-military. Referring to the "ever-reckless Bush-Cheney junta," Vidal

says, "Not since the 1846 attack on Mexico in order to seize California

has an American government been so predatory. . .He is like a man in one

of those dreams who knows he is safe in bed and so can commit any crime he

likes in his voluptuous alternative world."

After this piece comes a number of earlier essays, including his much more

substantial "State of the Union: 1980." The essay "Note on Our Patriarchal

State," which appeared in The Nation in 1990, has a new postscript on the

Pledge of Allegiance controversy currently before the Supreme Court. The

book ends with another new piece of writing, "Interim Report: Election

2004," in which Vidal argues that "a feckless Bush has not only given new

meaning to the equally feckless Democratic party but he has, despite the

best - that is, worst - efforts of the media, given new meaning to our

corrupt political system as the United States is now starting to divide,

consciously, between imperialists, eager for us to seize all of the

world's oil resources, and the anti-imperialists who favor peace along

with renewable sources of energy." The essay, and the book, ends with a

nod to Dennis Kucinich, "the most eloquent of the presidential candidates

this year," whom Vidal sees as "the natural leader of an as-yet-unborn

progressive alliance." Time will tell if this prognostication comes true.

Conversations

with Gore Vidal (2005)

Published as part of the "Conversations with" series of the University

Press of Mississippi, this book collects 11 interviews with Vidal culled

from decades worth of material and covering a wide range of topics

(literature, politics and sexuality get a lot of attention). The book also

has a chronology of Vidal's life and work and an index to the interviews.

It comes in two editions - a trade paperback ($20) and a jacketless

hardcover ($50) intended for libraries - and had a first printing of 2,000

copies. The interviewers include such notables as Larry Kramer ("The

Sadness of Gore Vidal"), Gerald Clarke ("The Art of Fiction"), and Hollis

Alpert and Jan Kadar ("Dialogue on Film"). And the book contains a

shortened version of my

own 1991 interview with Vidal.

Point to Point Navigation: A Memoir

(2006)

Compared to Palimpsest - Vidal's earlier memoir, which covered

the first 40 years of his life - this closing chapter in his life story is

a minor work in a minor key. Vidal is more anecdotalist than memoirist

this time, although he tells a wonderful story. The book is 263 pages long

where Palimpsest was 419, and about half of the anecdotes in the

new book have appeared elsewhere in his writing - in the first memoir, in

some autobiographical essays, and in his political writings (portions of

Point to Point Navigation do public policy rather than personal

history, perhaps because, in Vidal's latter years, the two have become so

intertwined). His storytelling is peripatetic, although he always makes

connections when he moves back and forth in time. Hence the meaning - or

one of them, anyway - of his title. Still, it's almost 30 pages before he

gets to something new in the book, and a few times, when he

repeats stories from the earlier memoir, he ultimately notes that he's

doing so.

The book's most moving passages revolve around the illness, decline and

2003 death of Howard Austen, who lived with Vidal for 53. His stories of

Howard are largely unsentimental, and yet, they turn the lion into the

lamb. At the end of Palimpsest, in which he often spoke of Jimmie

Trimble, his boyhood lover, Vidal declared the book to be a love story.

This is no less true of Point to Point Navigation, although

because this love is older, longer and of a different nature (they shared

everything but sex), it's understandably much more private. Agape usually

is.

As for the rest of his anecdotes, they're probably best taken with a large

grain of salt water. At least twice in the book, Vidal is embarrassingly

wrong about things. He has long hated The New York Times, and rightfully

so, after the daily Times refused to review his novels that followed the

publication of The City and the Pillar in 1948. But ire is no

reason to err. In the new memoir, Vidal recounts two details of a 1960

New York Times "hatchet job" about his run for Congress that are not, in

fact, a part of the article as he claims. Whether Vidal came off looking

good or bad in the article is a matter of opinion, although he deftly

answers every charge of his opponent. But the reporter did not

say Vidal chain smoked, as Vidal writes in his memoir, nor did the

reporter get Vidal's eye color wrong.

More disturbing is a lovely passage in which Vidal describes watching Neil

Armstrong's July 20, 1969, moon walk with his dying father, Gene Vidal,

who was a pioneer in the aviation industry. Trouble is, Gene Vidal died on

Feb. 20, 1969 - exactly five months before the historic event took

place. There is no indication whatsoever that Vidal intended this passage

in his book to be taken as dream or metaphor. It's odd that his fact

checkers at Doubleday didn't catch the error, but it's odder still that

Vidal thinks it actually happened. He writes:

Father and son equally gasped as a hollow voice told us that this was

a small step for man but a giant step for mankind . . . Gene was amused:

"I can just see the wars over who gets the mineral rights to the moon."

But he was delighted to be still alive at the moment. . . . "I always knew

we were headed for the moon and beyond but I never thought that I would

live to see it." He did by some months.

How, then, are we to take the rest of the tales in his book, even if Vidal

does remind us that memory is imperfect. Decide for yourself.

Point to Point Navigation is imbued with talk and thoughts of

death, with Vidal often joking about answering his own Grim Reaper's knock

at the door. He ends his life story - and, perhaps, his life as a writer -

with a six-line passage from Pope's Dunciad that concludes:

Light dies before thy uncreating word;/Thy hand, great Anarch, lets

the curtain fall,/And universal Darkness buries all. This sounds

ominously like a poem that the 16-year-old Vidal published in his high

school literary journal. "We are lost to hope and God," the proto-atheist

wrote. "For the night is black, no light but night, no God." Full circle.

Selected Essays (2007)

The Selected Essays of Gore Vidal (2008)

These are essentially the same book: The former is a paperback published

in the United Kingdom, and the latter is a hardback published in the

United States. The U.K. edition has 21 essay, the U.S. edition has 24.

They all were chosen by Jay Parini, Vidal's friend and literary executor,

who wrote an introduction to accompany his selections.

Parini calls Vidal "American's premier man of letters" with "a unique

voice whose luminous, excoriating, funny, and informative essays may well

be regarded by future generations as the pinnacle of his achievement." He

also notes that "Vidal is conservative in many respects, asking only for

liberty in the eighteenth-century sense of that term. He stands behind

individual choices, the limitations of executieve power, and the

preservation of the environment. Always the iconoclast," Parini says,

"Vidal has a particular distaste for piety in its American

manifestations."

Each book leads with the oldest essay, "Novelists and Critics of the

1940s," which first appeared in 1953 in New World Writing #4, a

literary anthology of the time. Each ends with the most recent one, "State

of the Union: 2004," which appeared in The Nation. A little more

than half of the book's essays are about literature (Updike, Dawn Powell,

Calvino, Williams), and the rest are about politics, history and culture

(Teddy Roosevelt, gay rights, national security, Sept. 11, pornography).

Unique to the American edition is "The Holy Family," Vidal's excellent

1967 essay about the Kennedys; a refletion on Edmund Wilson; and "Tarzan

Revisited," his 1963 treatise on the jungle man and related issues.

Each book leads with the oldest essay, "Novelists and Critics of the

1940s," which first appeared in 1953 in New World Writing #4, a

literary anthology of the time. Each ends with the most recent one, "State

of the Union: 2004," which appeared in The Nation. A little more

than half of the book's essays are about literature (Updike, Dawn Powell,

Calvino, Williams), and the rest are about politics, history and culture

(Teddy Roosevelt, gay rights, national security, Sept. 11, pornography).

Unique to the American edition is "The Holy Family," Vidal's excellent

1967 essay about the Kennedys; a refletion on Edmund Wilson; and "Tarzan

Revisited," his 1963 treatise on the jungle man and related issues.

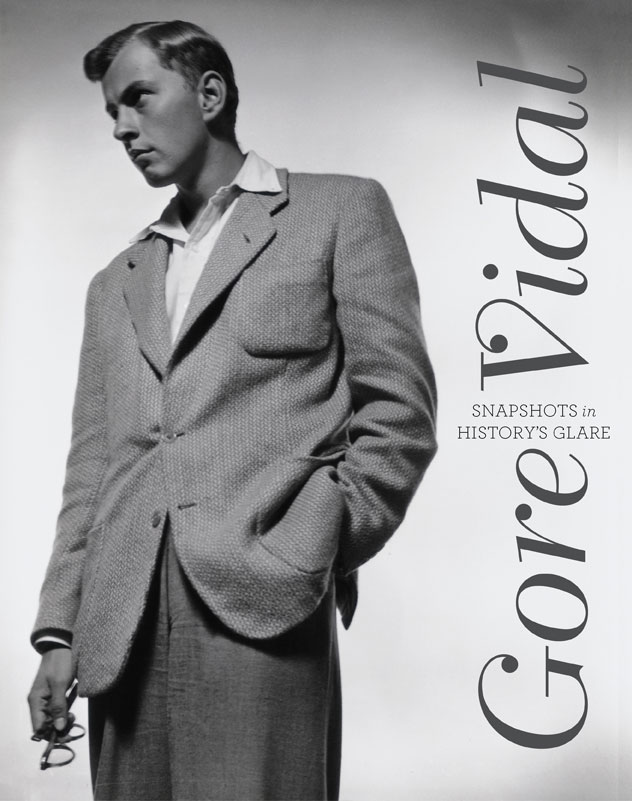

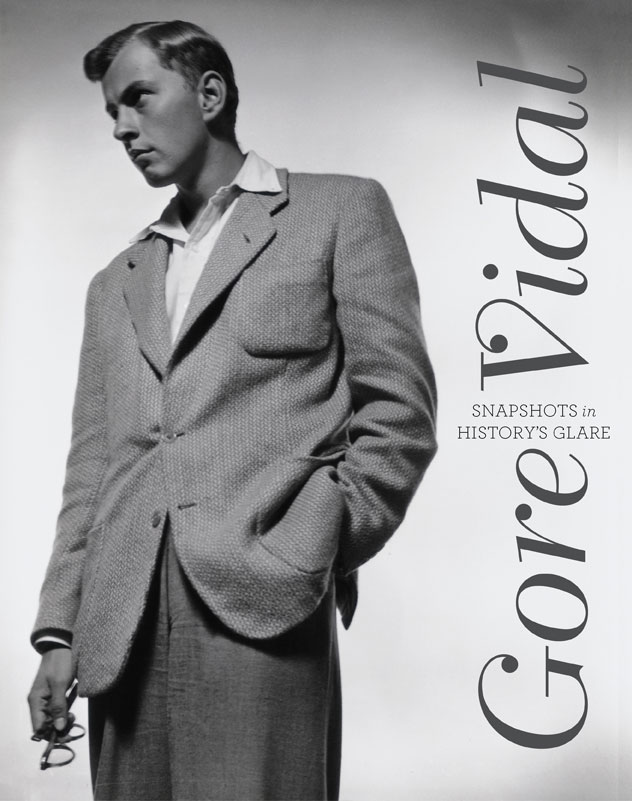

Snapshots in History's Glare (2009)

This unusual book recalls Vidal's life largely in pictures culled from his

archives, many of them never before shown to the public. Ann Schneider, a

photo editor at Vanity Fair magazine, collaborated with Vidal in selecting

and arranging the photos for the book. The web site Gawker

wrote a piece on the book with many photos of Vidal, both old and new (and

animated and risque). This is Vidal's third memoir, and he wrote it as a

tribute to his long-time companion Howard Austen, who died a few years

ago. Howard was the archivist of the relationship, although Vidal clearly

enjoyed being photographed.

The

publisher describes the book this way: "This book is Gore Vidal's

visual memoir of his remarkable and famously well-lived life. In this

collection of photographs, letters, manuscripts, and other selections from

Vidal's vast personal archives, readers are now escorted by one of

America's wittiest insiders into the Kennedys' Camelot, as well as onto

the set of Ben Hur, and into the private lives of Eleanor

Roosevelt, Paul Newman, and Tennessee Williams, to name just a few. Born

into public life, here Vidal looks back on his days as an Army officer in

WWII, his rise as a groundbreaking and controversial novelist, his years

in Hollywood, his forays into the political arena, and his notoriously

public triumphs and feuds. Written with Vidal's legendary wit and literary

elegance, this book reveals not only the personal reflections of one of

the last of the great generation of American writers, but also a

captivating social history of the 20th century told by one of our great

raconteurs."

The

publisher describes the book this way: "This book is Gore Vidal's

visual memoir of his remarkable and famously well-lived life. In this

collection of photographs, letters, manuscripts, and other selections from

Vidal's vast personal archives, readers are now escorted by one of

America's wittiest insiders into the Kennedys' Camelot, as well as onto

the set of Ben Hur, and into the private lives of Eleanor

Roosevelt, Paul Newman, and Tennessee Williams, to name just a few. Born

into public life, here Vidal looks back on his days as an Army officer in

WWII, his rise as a groundbreaking and controversial novelist, his years

in Hollywood, his forays into the political arena, and his notoriously

public triumphs and feuds. Written with Vidal's legendary wit and literary

elegance, this book reveals not only the personal reflections of one of

the last of the great generation of American writers, but also a

captivating social history of the 20th century told by one of our great

raconteurs."

I Told You So: Gore Vidal Talks Politics

(2013)

Over the course of 20 years, the journalist Jon Wiener interviewed Vidal

many times, and now he's collected four of those lengthy interviews in

this 160-page book that focuses on Vidal's political views. The oldest of

the four is from 1988, the most recent from 2008, before the election of

Barack Obama, and together, they allow Vidal to talk about a wide range of

subjects.

Over the course of 20 years, the journalist Jon Wiener interviewed Vidal

many times, and now he's collected four of those lengthy interviews in

this 160-page book that focuses on Vidal's political views. The oldest of

the four is from 1988, the most recent from 2008, before the election of

Barack Obama, and together, they allow Vidal to talk about a wide range of

subjects.

Here's a sample of what Vidal had to say about money in politics

during the 2000 presidential election between Al Gore and George W. Bush:

"There isn't one person in America who has ever thought about politics

who doesn't know that every single member of Congress is paid for by

corporate America, and it isn't to represent the people of their state, it

is to represent corporate America's interests, which are not those of the

people at large. So, they've given up on the idea of having

representatives in Congress. They see two candidates this year [Gore and

Bush] who, whatever their plusses or minuses, represent nothing at all

that has to do with the people. These are people who go to fundraisers,

who create fundraisers. Bush became the Republican candidate because he

has the same name as a failed president, and he got $70 million on the

strength of that from corporate America. Gore is running neck and neck

with him."

Gore Vidal's State of the Union: The Nation Essays

1958-2008 (2013)

Edited by Richard Lingeman

Vidal wrote many essays for many publications from the 1950s until a few

years before his death. But nowhere was he at his most fiery and liberal

than in The Nation, a journal that would often publish essays no other

magazine would touch.

All of the writing in this assemblage - which is available only in a

Kindle edition - appear in other books of his collected essays. But

they're still some of his most assertive and trenchant work. "Some Jews

and the Gays" caused a stir, and such essays as "Requiem for the American

Empire" and "Monotheism and Its Discontents" show the many tentacles of

his intellect. Nation Books, a publishing arm of the magazine, also

published two of Vidal's post-Sept. 11 books, Perpetual War for

Perpetual Peace and Dreaming War. The former began as an

essay written for Vanity Fair that the magazine subsequently rejected.

Buckley vs. Vidal (2015)

Edited by Tom Graves

Introduction by Robert Gordon

In 1968, before the copious (perpetual?) punditry spawned by 24-hour news

channels with time to fill and nothing to fill it with, a live political

debate on television was something rare. So when ABC News hired Gore Vidal

and his conservative counterpart, William F. Buckley Jr., to conduct a

series of political debates during the presidential conventions, it became

must-see TV.

In 1968, before the copious (perpetual?) punditry spawned by 24-hour news

channels with time to fill and nothing to fill it with, a live political

debate on television was something rare. So when ABC News hired Gore Vidal

and his conservative counterpart, William F. Buckley Jr., to conduct a

series of political debates during the presidential conventions, it became

must-see TV.

The debates began in Miami, during the Republican convention, and then

continued a week later in Chicago, at the Democratic bacchanal. There were

eight in all, and as the political tensions grew in a divided nation, the

exchanges between the two long-time ideological rivals became more

acrimonious.

This book, edited by Tom Graves, and with an introduction by Robert Gordon, has

transcribed the debates to let you read what the two men said to each

other, with ABC newsman Howard K. Smith moderating. Gordon and Morgan

Neville co-wrote and co-directed Best of

Enemies (2015), a documentary that mines the tapes of the debates

and tells their story with clips and narration.

For all of the substance that came forth during the two men's exchanges,

surely nothing was more memorable than the moment when Vidal called

Buckley a Nazi and Buckley countered by calling Vidal a "queer." It

happened on Aug. 27, 1968. (Listen to the full 22-minute

debate.) Looking back now, most historians conclude that Vidal got the

upper hand, and Buckley seemed to know it. But in the moment of that

exchange, watch Vidal's face: He manages an uncomfortable

smile, clearly shocked at having been outed on national television.

The exchange went like this:

VIDAL: There are many people in the United States [who] happen to believe

that the United States' policy is wrong in Vietnam and the Vietcong are

correct in wanting to organize their country in their own way politically.

This happens to be pretty much the opinion of Western Europe and many

other parts of the world. If it is a novelty in Chicago that is too bad. I

assume that the point of American democracy is you can express any point

of view you want.

BUCKLEY: (garbled)

VIDAL: Shut up a minute.

BUCKLEY: No, I won't. Some people are pro-Nazi and the answer is that

they were well-treated by people who ostracized them and I am for

ostracizing people who egg on other people to shoot American marines and

American soldiers. I know you don't care.

VIDAL: As far as I am concerned, the only pro- or crypto-Nazi I can

think

of is yourself, failing that, I would only say that we can't have.

HOWARD K. SMITH: Let's stop calling names.

BUCKLEY: Now listen, you queer. Stop calling me a crypto Nazi or I'll

sock you in your goddamn face and you'll stay plastered.

With all due respect to Carville and Matalin, we don't get TV debates like

that any more.

Gore Vidal: His Essential Quotations (2016)

Edited by Andrew Delaplaine

"There is no human problem that could not be solved," Gore Vidal once

said, "if people would simply do as I advise." And that was one of his

more modest declarations.

"There is no human problem that could not be solved," Gore Vidal once

said, "if people would simply do as I advise." And that was one of his

more modest declarations.

In this slim but entertaining volume, Andrew Delaplaine has brought

together a cornucopia of Vidalian observations, declarations and

proclamations on politics, history, culture, sex and himself. The book

begins with what might be its epigram: "Style is knowing who you are, what

you want to say, and not giving a damn." Vidal spent more than half a

century demonstrating what he meant.

A few more samples:

- "When I arrived for the filming of Ben-Hur, all the sets had

been built, including Charlton Heston."

- "American society, literary or lay, tends to be humorless. What

other culture could have produced someone like Hemingway and not seen the

joke"?

- "Whenever a friend succeeds, a little something in me dies."

- "It is not enough to succeed. Others must fail."

And finally, in case you think he only said what he said to give people

a smile and something to think about: "I am exactly as I appear. There is

no warm lovable person inside. Beneath my cold exterior, once you break

the ice, you find cold water."

Vidal vs. Mailer (2016)

Edited by Carole Mallory

This promises to be one of the more unusual compilations of Vidal's

writing - if it ever materializes. Originally announced for 2014, it's now

been put back until the end of 2016. (Must be the lawyers.) It's a

collection of writings by the two authors that revolve around their

decades-long feud. Mallory was Norman Mailer's mistress for about a decade

beginning in the early 1980s, and in 2010, three years after his death,

she released a memoir called Loving Mailer.

This promises to be one of the more unusual compilations of Vidal's

writing - if it ever materializes. Originally announced for 2014, it's now

been put back until the end of 2016. (Must be the lawyers.) It's a

collection of writings by the two authors that revolve around their

decades-long feud. Mallory was Norman Mailer's mistress for about a decade

beginning in the early 1980s, and in 2010, three years after his death,

she released a memoir called Loving Mailer.

Melville House, the book's publisher, describes it like this: "The feud, from a time when writers

really mattered in American public life, is the stuff of literary legend,

and Vidal vs. Mailer collects the exchanges, transcripts and interviews

that document the historic rivalry. Their 1971 confrontation on the Dick

Cavett show is probably the most famous literary encounter ever captured

by television. The on-air badinage between the two was shockingly nasty,

but some reports say it was even worse backstage, where Mailer reportedly

headbutted Vidal in Cavett's greenroom. At the climax of the feud in the

late 1970s, Mailer encountered Vidal at a party thrown by Lally Weymouth

and promptly flattened him with a punch. At which point Vidal, still on

the floor, uttered what is perhaps the most immortally apt literary

criticism ever: 'Once again, words have failed Norman Mailer.'"

By 1991, the feud had ended, and the two men got together for a joint

interview published in Esquire. Mallory's book revisits this fiery

passage in American literary history.

Return to the Gore Vidal

Thumbnails introduction

Return to the Gore Vidal

Thumbnails introduction

If you came right to this thumbnail page and don't see a frame on the

left, please visit The Gore Vidal

Index now or after you've enjoyed the thumbnails, which you can access

from the main index page. And please send me comments if you have a thought, a suggestion

or a link to add to the index.

©Copyright 2005 by

Harry Kloman

University of Pittsburgh

kloman@pitt.edu

Just as Vidalís work as a

playwright and screenwriter came

about in part through financial necessity, so did his work as an essayist.

In the early 1950s, he found that he could make some extra income writing

for magazines and journals, and so he did. Soon he came to enjoy this

role, although he could not have known these little pieces - which grew

bigger as time went on - would bring him perhaps his widest fame. Many

Vidal enthusiasts now consider his essays to be more important

than his

novels, and even those who like his novels realize that they expound upon

the themes he examines so well in his critical nonfiction. A number of

European publishers have enjoyed and published Vidalís essays, although

surprisingly, not as widely as his novels. His essays have been

periodically translated into French, German, Spanish, Italian, Portuguese,

Serbian and Hungarian. Heís also a popular commentator in the United

Kingdom, where all of his American essay collections have appeared, along

with a few unique British collections.

Just as Vidalís work as a

playwright and screenwriter came

about in part through financial necessity, so did his work as an essayist.

In the early 1950s, he found that he could make some extra income writing

for magazines and journals, and so he did. Soon he came to enjoy this

role, although he could not have known these little pieces - which grew

bigger as time went on - would bring him perhaps his widest fame. Many

Vidal enthusiasts now consider his essays to be more important

than his

novels, and even those who like his novels realize that they expound upon

the themes he examines so well in his critical nonfiction. A number of

European publishers have enjoyed and published Vidalís essays, although

surprisingly, not as widely as his novels. His essays have been

periodically translated into French, German, Spanish, Italian, Portuguese,

Serbian and Hungarian. Heís also a popular commentator in the United

Kingdom, where all of his American essay collections have appeared, along

with a few unique British collections.

written by Ray Lewis White. Six years later came two books: Bernard F.

Dickís The Apostate Angel: A Critical Study of Gore Vidal; and

Myra & Gore: A Book for Vidalophiles, by John Mitzel with Steven

Abbott, consisting of a socio-sexual reading of Myra Breckinridge

and a lengthy interview with Vidal reprinted from the journal Fag

Rag. Robert F. Kiernan published another eponymous critical study in

1983; Jay Parini, Vidalís literary executor, compiled Gore Vidal:

Writer Against the Grain, a collection of scholarly essays, in 1992;

and Susan Baker and Curtis S. Gibson published Gore Vidal: A Critical

Companion in 1997, offering a series of original essays on Vidalís

books from various critical perspectives (deconstructive, feminist,

Marxist, new historicist, etc.). Finally, for those fluent in French,

thereís Nicole Bensoussanís Gore Vidal: líiconoclaste, a 1997

critical study, not yet translated into English, that covers everything

from Myra and the other inventions to the novels of ancient

and American history.

written by Ray Lewis White. Six years later came two books: Bernard F.

Dickís The Apostate Angel: A Critical Study of Gore Vidal; and

Myra & Gore: A Book for Vidalophiles, by John Mitzel with Steven

Abbott, consisting of a socio-sexual reading of Myra Breckinridge

and a lengthy interview with Vidal reprinted from the journal Fag

Rag. Robert F. Kiernan published another eponymous critical study in

1983; Jay Parini, Vidalís literary executor, compiled Gore Vidal:

Writer Against the Grain, a collection of scholarly essays, in 1992;

and Susan Baker and Curtis S. Gibson published Gore Vidal: A Critical

Companion in 1997, offering a series of original essays on Vidalís

books from various critical perspectives (deconstructive, feminist,

Marxist, new historicist, etc.). Finally, for those fluent in French,

thereís Nicole Bensoussanís Gore Vidal: líiconoclaste, a 1997

critical study, not yet translated into English, that covers everything

from Myra and the other inventions to the novels of ancient

and American history.

The

publisher describes the book this way: "This book is Gore Vidal's

visual memoir of his remarkable and famously well-lived life. In this

collection of photographs, letters, manuscripts, and other selections from

Vidal's vast personal archives, readers are now escorted by one of

America's wittiest insiders into the Kennedys' Camelot, as well as onto

the set of Ben Hur, and into the private lives of Eleanor

Roosevelt, Paul Newman, and Tennessee Williams, to name just a few. Born

into public life, here Vidal looks back on his days as an Army officer in

WWII, his rise as a groundbreaking and controversial novelist, his years

in Hollywood, his forays into the political arena, and his notoriously

public triumphs and feuds. Written with Vidal's legendary wit and literary

elegance, this book reveals not only the personal reflections of one of

the last of the great generation of American writers, but also a

captivating social history of the 20th century told by one of our great

raconteurs."

The

publisher describes the book this way: "This book is Gore Vidal's

visual memoir of his remarkable and famously well-lived life. In this

collection of photographs, letters, manuscripts, and other selections from

Vidal's vast personal archives, readers are now escorted by one of

America's wittiest insiders into the Kennedys' Camelot, as well as onto

the set of Ben Hur, and into the private lives of Eleanor

Roosevelt, Paul Newman, and Tennessee Williams, to name just a few. Born

into public life, here Vidal looks back on his days as an Army officer in

WWII, his rise as a groundbreaking and controversial novelist, his years

in Hollywood, his forays into the political arena, and his notoriously

public triumphs and feuds. Written with Vidal's legendary wit and literary

elegance, this book reveals not only the personal reflections of one of

the last of the great generation of American writers, but also a

captivating social history of the 20th century told by one of our great

raconteurs."

Over the course of 20 years, the journalist Jon Wiener interviewed Vidal

many times, and now he's collected four of those lengthy interviews in

this 160-page book that focuses on Vidal's political views. The oldest of

the four is from 1988, the most recent from 2008, before the election of

Barack Obama, and together, they allow Vidal to talk about a wide range of

subjects.

Over the course of 20 years, the journalist Jon Wiener interviewed Vidal

many times, and now he's collected four of those lengthy interviews in

this 160-page book that focuses on Vidal's political views. The oldest of

the four is from 1988, the most recent from 2008, before the election of

Barack Obama, and together, they allow Vidal to talk about a wide range of

subjects.