A little over half way through the third video (at 8 min 50 sec), you will see it. I'm sailing up the Allegheny towards the Fort Duquesne Bridge. When I am under the bridge, I decide to turn back. The best winds are downstream from the bridge. To turn back, I need to tack. That means that I will turn the bows of the boat through the wind. If I succeed, I will make the transition from the wind blowing over my port (left) side, to the wind blowing over my starboard (right) side. In short, I will have "changed tack" and made it to the "other tack."

You will see in the video that I do not make it and, after a second try, end up sailing at some speed towards the bridge pylon.

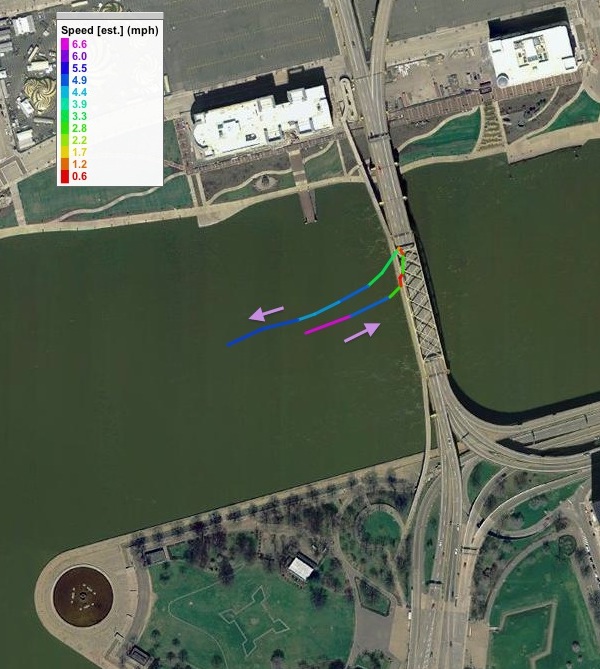

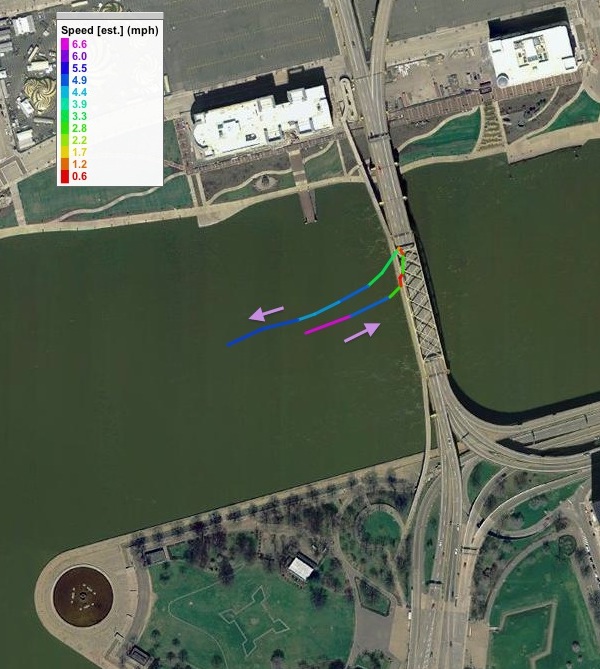

Here's the portion of the gps track that shows it.

What happened?

First, tacking is always a little delicate. When your bows are pointing directly into the wind, there's nothing powering the boat. It can stall there and you are "in irons." You rely on getting enough speed prior to the tack so that your momentum carries you past the awkward moment when your bows point directly into the wind.

On mono-hull boats (i.e. not catamarans), tacking is easier. They have a centerboard and the boat swivels around it fairly easily. A catamaran like the Hobie Bravo has no centerboard. Instead, the full length of the hull provides the sideways resistance that a sailboat needs.

Using the full length of the hull for resistance makes turning harder. Think of a knife thrust into the water. If it is thrust in vertically (the mono-hull case), it is easier to turn. But if it lies horizontally in the water with the cutting edge of the blade facing the bottom of the river, it is much harder to turn.

That was not the real problem. I was the problem. I'd misjudged the wind.

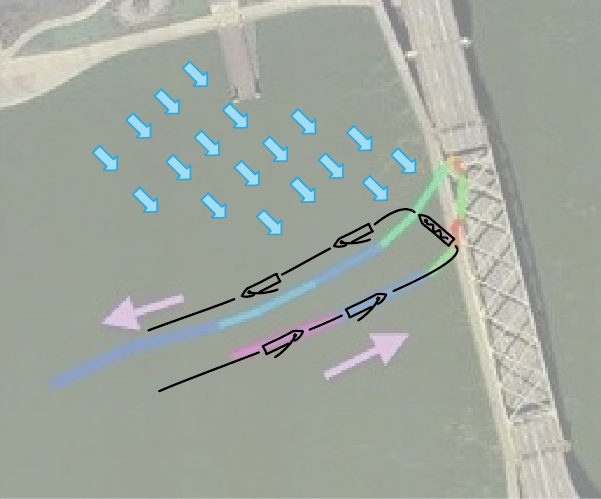

While I was approaching the bridge, the wind had been blowing roughly from the Northwest. I'd assumed that, when I was under the bridge, it would keep that direction. This is how I'd conceived the maneuver. The blue arrows show what I thought was the wind direction.

I'd expected to be able to turn to a Northwest pointing course, where I'd be pointing straight into the wind. My momentum would carry me past that direction and I'd end up on the opposite tack, sailing back down the river.

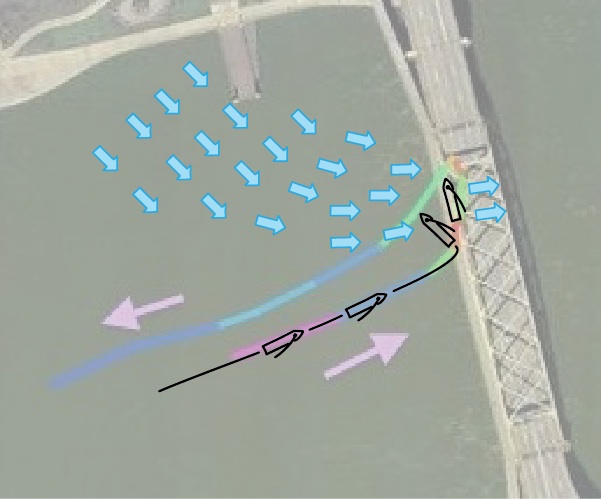

What I'd not noticed or realized was that the wind was being redirected by the bridge. It is a big structure that will block the wind and funnel it under and around its span. The net effect was that the wind near the bridge had been turned to blow from the West. So when I'd turned the boat to the Northwest, I had not turned it far enough for the momentum of boat to keep it moving past the direction of the wind. But I'd gotten close enough to the wind to lose power and stop.

Here's how the wind was really directed and what really happened.

I had not turned far enough to make it to the other tack. The boat stalled and stalled again on a second attempt. The way to get back up to speed was to turn away from the wind and let the wind accelerate the boat on a Northerly course. That is what I did.

But that meant sailing directly towards the bridge pylon. It does look a little dangerous, sailing directly at a very solid, stone wall. But it's actually quite safe.

Small boats are more robust than big boats. A toy Titanic in the bathtub can hit every other toy without hurting itself. The full-sized Titanic just needed to scrape an iceberg to be doomed. Even if my little boat hit the wall head on, the worst damage is likely to be my bruised ego, although I'll not try the experiment. There was no danger it would happen. A small boat like this can turn on a dime and I did turn at the last moment.

The only real danger was that I would stall next to the pylon and the wind would slowly blow me against it. I have done that before.

John D. Norton